Deep Dive: Neutral

Nate Helbach is aiming to succeed where other construction tech innovators have failed

Today’s Thesis Driven is the second in a series of deep dives into specific innovative companies. You can see our first deep dive, into fractional homebuying platform Ownify, here.

The past five years have not been kind to construction tech companies. With massive flameouts like Katerra and Veev, construction tech is a veritable graveyard of venture-backed startups. But the push for innovation hasn’t ceased, with new companies looking to learn the lessons of those failures and explore new approaches.

Today’s letter will explore Neutral, a company aiming to learn from the past decade of venture-backed startup failures by taking a different, more iterative approach to real estate development and project capitalization. As the venture path becomes tougher, it’s instructive to dig into alternative approaches like Neutral’s, particularly those that mix-and-match elements from both traditional and innovative models.

This letter will explore Neutral’s strategy and plans, including the firm’s:

Thesis and approach;

Projects and real estate development track record;

Use of mass timber and other innovations;

Capitalization strategy.

A Neutral Thesis

Like many construction tech innovators, Neutral founder Nate Helbach started the firm with the goal of decarbonizing construction. Construction is, after all, the single largest contributor to carbon dioxide emissions, accounting for 42% of all emissions globally. To adopt a more sustainable approach, Neutral planned to deploy new materials and techniques popular outside the United States to build more efficiently and—perhaps—cost-effectively.

But that’s where parallels between Neutral and some of the companies mentioned earlier—such as Katerra and other modular and pre-fab construction tech startups—cease. For one, Neutral didn’t start with a new construction product or methodology and then attempt to sell it to developers and investors. Instead, Helbach chose to build Neutral as a real estate developer first. Rather than creating a real estate development company inside a venture-backed OpCo wrapper—like many new construction technology companies—Helbach adopted a more traditional real estate development company structure and capitalizing approach for Neutral. As we'll explore, Helbach sought to combine a tech company's product mindset and vertical integration with a real estate development company's capital structure and philosophy.

“A lot of people have taken a disruptive approach, but we’re taking an iterative approach,” explains Helbach. “We said, ‘Let’s continue to build buildings in the model we can build buildings today, but let’s iterate to a future that’s different.’”

While off the venture capital radar, Neutral has begun to assemble a real estate development track record—and they’re not starting small. The company’s first project, Baker Place in Madison, Wisconsin, set to open in April of 2025, is the city’s first mass timber high-rise at 14 stories and 206 units. And their sights are set even bigger, with construction of Milwaukee’s The Edison (32 stories, 383 units) scheduled to begin in late 2024; Neutral also recently proposed a 55 story, 750-unit tower that would be the tallest mass timber building in the world.

The company started its first low-rise real estate product in August 2024 in Madison, Wisconsin, using a componentized system approach to development that Neutral's in-house architecture and technology team developed.

As we’ll discuss, mass timber has been a recurring theme in all of Neutral’s projects to date. Rather than start by building proprietary technology, Helbach chose to use existing technologies and materials—like mass timber—that weren’t yet seeing broad adoption in the US development market and bring them to market at scale.

The Role of Mass Timber

Neutral development manager (and occasional Thesis Driven contributor) Fed Novikov penned a detailed overview of mass timber construction in Thesis Driven earlier this summer. The letter was up-front about the challenges–as well as opportunities–of mass timber construction, detailing Neutral’s firsthand experience.

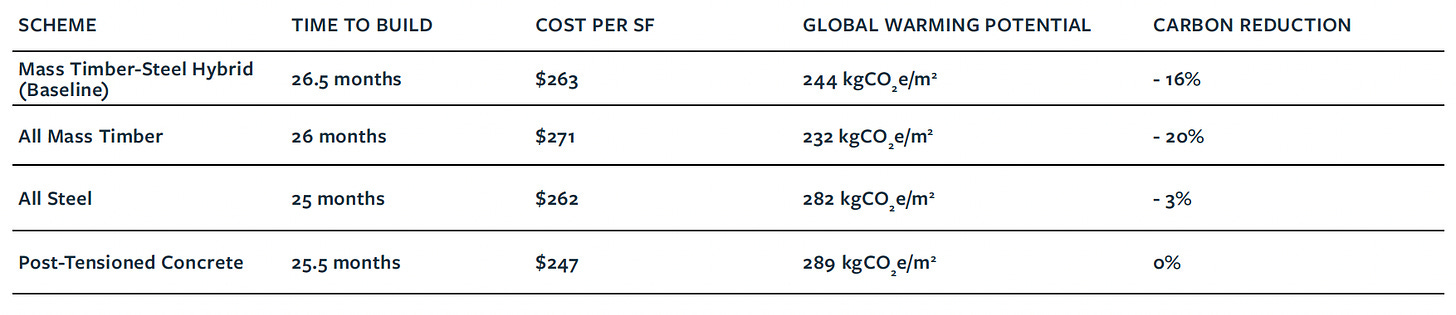

While mass timber has substantial benefits from a sustainability standpoint, it doesn’t offer much (yet) from the perspective of either cost or development timeline. As Novikov details, mass timber also raises both regulatory and insurance issues, with many US-based insurers unwilling to underwrite mass timber construction. (Neutral solved this particular issue by working with a European reinsurance company that is more familiar with mass timber than its US peers.)

But alongside other regenerative materials—such as biochar, wool, wood, and terracotta, for example—Neutral can craft a sustainability case for their projects, with the ultimate goal of winning certifications such as Passive House Institute United States (PHIUS) and Living Building Challenge (LBC). The thesis, as laid out in our letter on mass timber, goes something like this:

An increasing number of institutional investors worldwide – mainly in Europe but also in North America – are implementing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards for new as well as existing assets in their portfolios. This is in response to government regulations and investor-imposed impact mandates.

For real estate, these mandates mean that within the next ten years, there will be an imbalance in supply and demand between institutional demand for sustainable assets and their relative lack of supply in the North American market.

This imbalance creates an opportunity for developers to meet the coming demand by building sustainable assets today. For long-term holders, the benefits of paying more for sustainable building technologies up front could be justified by a compression on cap rates at sale, driving the purchase price up and thereby bringing higher returns to the project investors.

From Neutral’s perspective, it’s not as much about the technologies themselves as it is how they fit into the company’s overall approach, as we’ll discuss below.

An Iterative Philosophy

In addition to embracing new materials, Neutral has taken an unorthodox approach to vertical integration. While most small developers rely on third-party contractors and consultants for things like architecture and construction management , Neutral has chosen to vertically integrate, building its own architecture firm and design studio.

To Helbach, this vertical integration is part of Neutral’s iterative philosophy and development process. Per Helbach:

“We're designing a product instead of a one-off building that we design to build again, unlike most other real estate developers. If you look at different companies developing products like Toyota, Tesla, or Apple, they have internal teams that do the development and design work. The team is fully vertically integrated. Once the product is designed, they build a manufacturing facility and supply chain around that specific singular product. These companies would be insane to try and develop a different design for every customer they had who wanted to buy a new car or technology product from them. However, that is what the building industry has been doing for centuries. Neutral is taking an industrialized design and manufacturing approach with a vertically integrated team design and develop real estate products instead of one-off buildings.”

Helbach views Neutral’s vertical integration as key to the firm’s ability to scale over time, retaining learnings–and design components–from one building to the next.

"Industrialized componentized construction is only feasible when it begins in design,” says Helbach. “Once we have optimized the product design process, we can iterate to achieve economies of scale across multiple development projects. In turn, implementing more sustainable and industrialized construction products can be economically feasible."

Neutral views construction innovation as not just downstream of rethinking process and modularity in design, but actually implementing those modular designs using traditional construction methodologies first before moving anything onto an assembly line. “First, we design in a workable way for manufacturing,” says Helbach. “Then, we build it using traditional methods. Over time and with scale, we can move to a manufactured approach.”

In a sense, Helbach and Neutral are attempting to combine the scalable, product-oriented mindset of venture-backed technology firms with the iterative approach of traditional real estate developers, creating a syncretic philosophy that prioritizes systemization in design and process before industrialized construction.

Politically, this approach offers a major advantage: unlike other construction tech companies, Neutral’s approach doesn’t obviously displace local contractors and tradespeople. “Katerra basically said, ‘we’re doing everything offsite; go find a job elsewhere,’” said Helbach. This earned them enemies among the construction trades, creating another barrier to adoption in many markets. “We want to augment the construction trades instead of completely neglecting and omitting them from our new construction method.” Neutral aims to partner with the trades to make them more efficient, which is especially needed given the decline in skilled labor in the construction industry since 2007.

Capitalizing It All

Like its design approach, Neutral’s capitalization strategy reflects a different approach from the big names in construction tech. The company has eschewed venture capital, instead leaning heavily on family offices, high net-worth individuals, and even retail investors to capitalize its real estate projects.

This has allowed Helbach to reinvest the fee streams generated from Neutral’s developments into the company’s vertical integration, hiring architects, designers, and engineers out of fees. The most comparable model is probably Placemakr, which like Neutral raises real estate capital and generates fees on a deal-by-deal basis which it uses to fund its ongoing operations.

Notably, Neutral doesn’t raise capital on any of the public crowdfunding platforms. Rather, they focus on raising funds from high-net-worth individuals and retail investors from the cities in which they build. “Most of our project investors are accredited local people who want to be a part of our projects,” notes Helbach. “Bakers Place, for example, has 98 separate investors, the majority of them from Wisconsin.” Neutral has since launched an investor portal allowing national as well as local investors to back their projects; the software also provides investors more transparency through real-time updates on asset performance.

For their latest Milwaukee project, Helbach and his team send physical mailers to potential retail accredited investors across Wisconsin, recruiting them to in-person events at which details about the project are shared. “We do events every two weeks in Madison, Milwaukee, and Green Bay,” explains Helbach. “50-60% of our investor leads come from those events, and we now have a little over 200 investors across our portfolio.” Almost half (44%) of their accredited retail investors have invested in multiple Neutral projects.

Neutral’s focus on accredited retail investors has helped the company circumvent one of the biggest challenges that mass timber developers face. Like any new technology, mass timber is seen as an added risk by institutional equity investors, who are typically not willing to offer limited partner equity on mass timber projects when compared to those built with traditional construction methods. This is a big problem for PE-backed developers pressured to maximize returns. However, for many of Neutral’s retail investors, the differentiated product of mass timber is perceived as a benefit, not a risk. As we outlined in the prior section, Neutral believes that buildings built with mass timber will be differentiated in the marketplace and demand both a rental premium and compression on cap rates at sale, driving significantly higher returns than traditional construction methods.

To a lot of professional real estate investors, seeing a developer raise capital directly from retail investors automatically raises red flags. And I appreciate that, as retail crowdfunding is the tactic of choice for slimy syndicators and other bad actors.

But for me, Neutral’s focus on local investors flips that on its head. No developer wants to poison the well in their own backyard; if Neutral wants to continue building in Wisconsin, their local investor base will be a powerful force for—or against—them. In many ways, losing a pension fund’s money is a lot less fatal to a developer than angering hundreds of wealthy people in your own market.

Among construction tech companies, Neutral is taking an unorthodox approach. It eschews easy classification into the standard buckets of real estate developers, construction tech startups, or ESG-focused impact firms. It’s a bit of each and a bit of none of the above.

But in a space where the track record of peer companies is–to put it mildly–not great, untested approaches may be the best ones. At a minimum, Neutral’s avoidance of venture dollars (and venture expectations) in favor of a fee business supported by family offices and retail investors at the property level gives it an advantage over previous attempts.

After all, the downside case here is that Neutral merely continues on as a mid-size real estate developer, building the occasional sustainable project. But if Helbach’s firm can succeed at iterating their way into manufacturing economies of scale, they could fundamentally change how sustainable development happens.

—Brad Hargreaves