On Civil War

Thoughts on sorting, polarization, and what it all means for real estate and America. Happy July Fourth.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, every summer came packaged with a disaster movie theme. 1996 was all about tornadoes. 1997, volcanoes (several of them)! 1998 brought asteroids, with Deep Impact and Armageddon, and fires. These movies weren’t just relevant at the box office; each shaped a little national neurotic panic about its particular topic. The asteroid movie craze, for example, prompted more federal interest in the topic of “planetary defense,” while Twister spawned an entire decade of storm chasers and weather-related B-movies and late-night TV. As a child of the 90s, I spent far more time worrying about long-tail natural disasters than was probably healthy.

But the disaster movie wave soon subsided. The genre fell out of favor in the wake of 9/11, and the concept was soon edged out by the more esoteric moral panics of the 2000s. But the underlying pull of a good catastrophe story never fully subsided in a nation with a strong eschatological bent. For many of us, the end times are enticing—even if we know better.

So it’s interesting to see the disaster narrative re-emerge in summer 2024 in the form of a hypothetical second US civil war. While the film is neither particularly notable nor important on its own, it has framed a summer of dialogue about a national divorce over what appear to be unreconcilable political differences, increasing polarization, and gerontocracy.

For reasons we’ll discuss, I believe a bona fide “civil war”—the shooting kind—is highly unlikely. But there are reasons to believe partisan geographic sorting will accelerate rapidly in the coming years, with implications for anyone building in the physical world—especially those of us in the real estate industry.

Two Nations, One Country

America is unquestionably growing more polarized. This isn’t unique to the United States, of course, but it’s July 4th so we’ll focus here.

The polarization is happening simultaneously on two levels: individual voters as well as elected officials are each growing farther apart. Voters are more likely to have party-aligned and ideologically-consistent views, and party primary winners are more likely to be fully aligned with their parties’ positions—and, overall, more extreme.

While the causes of increasing polarization are outside the scope of this letter—we’re primarily interested in the second-order effects of polarization—it’s worth noting that the polarization trend maps neatly to the rising popularity of partisan-aligned 24/7 cable news (MSNBC and Fox, specifically) and social media. Specifically, I’d assume that the former is the primary driver behind increasing partisanship while the latter is responsible for rising fringe views—a different but related phenomenon.

Polarization is also increasingly geographic in nature. Twenty years ago, there were plenty of Democratic-leaning rural areas and at least a few Republican cities. Today, the former is extremely rare—parts of New England, resort destinations, and the Southern Black Belt, pretty much—and the latter is basically extinct. The number of competitive House districts has also decreased dramatically, and there are fewer “purple states.” While some of this is due to gerrymandering, the death of the competitive district has been accelerated by our own demographic sorting along partisan lines.

Geographic sorting—along with more time in social media content bubbles—has meant that American increasingly have negative views of people with differing political views. If a Republican voter has a Democratic-voting neighbor, they’re more likely to see Democrats as people, albeit misguided ones, and vice versa. But Americans are increasingly unlikely to have any friends with differing political opinions, entrenching division. This is the thesis behind The Big Sort, a prescient book that also underestimated the coming social media-fueled acceleration of its core premise.

Social media also makes a reversal of the polarization trend unlikely. Content filtering algorithms act as a ratchet, serving each user the content most likely to get them to engage. Often, this means steadily increasing doses of incendiary headlines and partisan rage-bait. Social algorithms are remarkably good at predicting adjacent content with which a user is likely to engage, and that new content is often slightly more extreme or aggressive than the original content. (After once watching a series of history videos about military campaigns in the medieval-era Middle East, YouTube convinced itself I was interested in converting to Islam.)

In the minds of many Americans, this division—along with political chaos at the federal level—sets the stage for a major national crisis.

To Arms?

A true “civil war” event—a shooting war or genuine national separation—strikes me as extremely unlikely for a few reasons.

One, Americans hate disorder, and the median American is pretty happy with his or her current lot in life. Americans predictably vote against disorder and upheaval; they’re beginning to punish the politicians who have allowed the worst excesses even in the most left-leaning cities.

Two, a genuine civil war would require a fissure in the US military. As Noah Smith wrote last year, that scenario seems far less likely than many on the left may fear:

Military personnel will continue to lean conservative, but esprit de corps and ideological commitment to the Constitution will prevent that conservatism from turning into Trumpism. And rightist demonization of the military will stiffen the brass’ resolve to resist future Trumpist encroachments. Also, because the military is consistently the country’s most trusted institution, the anti-military campaign will probably do the rightists few favors electorally.

Also, we can now be pretty sure that future coup attempts in America will not closely resemble 1930s Japan, and will not have similar outcomes. Recall that in Japan’s 1930s coups — the first of which were every bit as shambolic and doomed as the one on 1/6 — rightists created chaos in the hopes of forcing the civilian government to relinquish power to the military. Ultimately, though the coups were put down, the perpetrators succeeded in their objective. In the U.S., however, rightists know that giving the military dictatorial powers would work to their distinct disadvantage. And so they will attempt to seize power or create chaos by other means.

Continued acceleration of partisan geographic sorting seems a much more likely outcome—and one far easier to navigate. And there’s another big driver of sorting on the horizon: the 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court.

There are differing views on how explicitly partisan the 6-3 Supreme Court will be. But the Court will unquestionably take a more strict constructionist view of the US Constitution, which means that more powers will be devolved to the States. Naturally, this means that States will be able to adopt laws more in line with their partisan leanings. This is particularly true for red states, many of which have already rolled out strict abortion bans after the Dobbs decision; gay marriage, IVF, and even access to birth control may be on the table in some states in the future. I don’t see any of these attacks gaining serious traction beyond the margins, as things like birth control and IVF are overwhelmingly popular. But more power to the states means that some states are going to enact crazy laws.

While internal migration for political reasons is rare within the US today, growing differences between state laws will likely increase it in the coming years. What are minor partisan annoyances today—spats with neighbors and dwindling social circles—will become harder to ignore as emboldened state legislatures pass increasingly aggressive regulations.

Geographic sorting is already happening, of course. While most the more than 200,000 Californians that fled to Texas in 2021-22 did so for economic reasons, they also leaned heavily conservative. They weren’t just more right-leaning than the average Californian, but farther to the right than the average native-born Texan. Similarly, the massive number of conservative New Yorkers fleeing to Florida in recent years may have cost Republicans a surprisingly tight New York Governor’s race in 2022.

Like social media, geographic sorting has a ratchet effect, a positive feedback loop of partisanship. Right-leaning Californians moving to Texas are simultaneously making Texas more conservative and California more liberal, making each state more likely to enact laws that will further accelerate geographic sorting.

The Partition

The best historical analogy isn’t any civil war, US or Spanish or fictional. My bear case here is a far slower, far less violent version of the 1947 British Partition of India in which 14.5 million people moved over the course of several months. The British, by dividing the newly-created Indian and Pakistani states along the somewhat arbitrary Radcliffe Line, created a massive and sudden migration crisis in which religious minorities on the “wrong” side of the line moved en masse. Approximately a million people died during the Partition, most of them killed in sectarian violence.

I do not anticipate any similar mass casualty event in the United States. But the analogy is closer than it may initially appear. There is good reason to believe that politics has replaced religion with all of the Great Awakening’s fervor and fury. It does not seem outlandish that the next breakout of sectarian violence in the United States will be on the basis of politics, not God. Any acts of political violence, of course, would only serve to accelerate geographic sorting.

The silver lining of America’s federalist system is that geographic sorting alone doesn’t necessitate a national divorce. Devolution of powers allows states to enact the laws they wish—with some limitations. Of course, a divided nation is far harder to manage and is unlikely to pursue a coherent foreign policy, making this kind of division an attractive goal for our foreign adversaries, who have their thumbs on the scale of some of our biggest social media platforms.

Winning the Sort

Thus far, red states have significantly outperformed blue ones in our national Big Sort. Red states are dramatically outgrowing the rest of the nation, adding millions of new residents and political power through additional congressional seats and economic heft.

There’s one and only one reason for this: red states build. While there is plenty of demand to live in places like New York, Los Angeles, and even San Francisco, those cities chase residents away by refusing to build new housing. The result? Sky-high rents. The MSAs with the highest rents in the United States correlate tightly with those most Democratic-leaning.

If nobody wanted to live in these left-leaning cities—as many on the right claim—rents would be far lower. But it’s also correct that people who are politically misaligned with a place are the first to bail when the cost of living grows. So it’s both true that a lot of the people leaving New York and San Francisco are blaming the political environment and these cities would grow dramatically if they built more housing.

This circle gets squared by understanding that there’s a massive unmet demand for housing in New York and California by people who would like to move to those places from red states but can’t due to high housing costs. In other words, blue cities are terrible at accepting political refugees from red states. Red states, on the other hand, open the door to the politically aligned through abundant housing construction and low market-rate rents.

If state and local Democratic politicians really cared about the citizens of Republican-governed states who can’t get abortions or are seeing their voting rights suppressed, they’d first and foremost make it easier for those people to find refuge in friendlier cities. Instead, they tell newcomers to “go back to Iowa and Ohio” and disparage arrivals as “trust fund transplants from the Midwest.” Others on the far left have embraced a form of blood-and-soil nativism, discouraging internal migrants (“gentrifiers”) from moving to affordable neighborhoods.

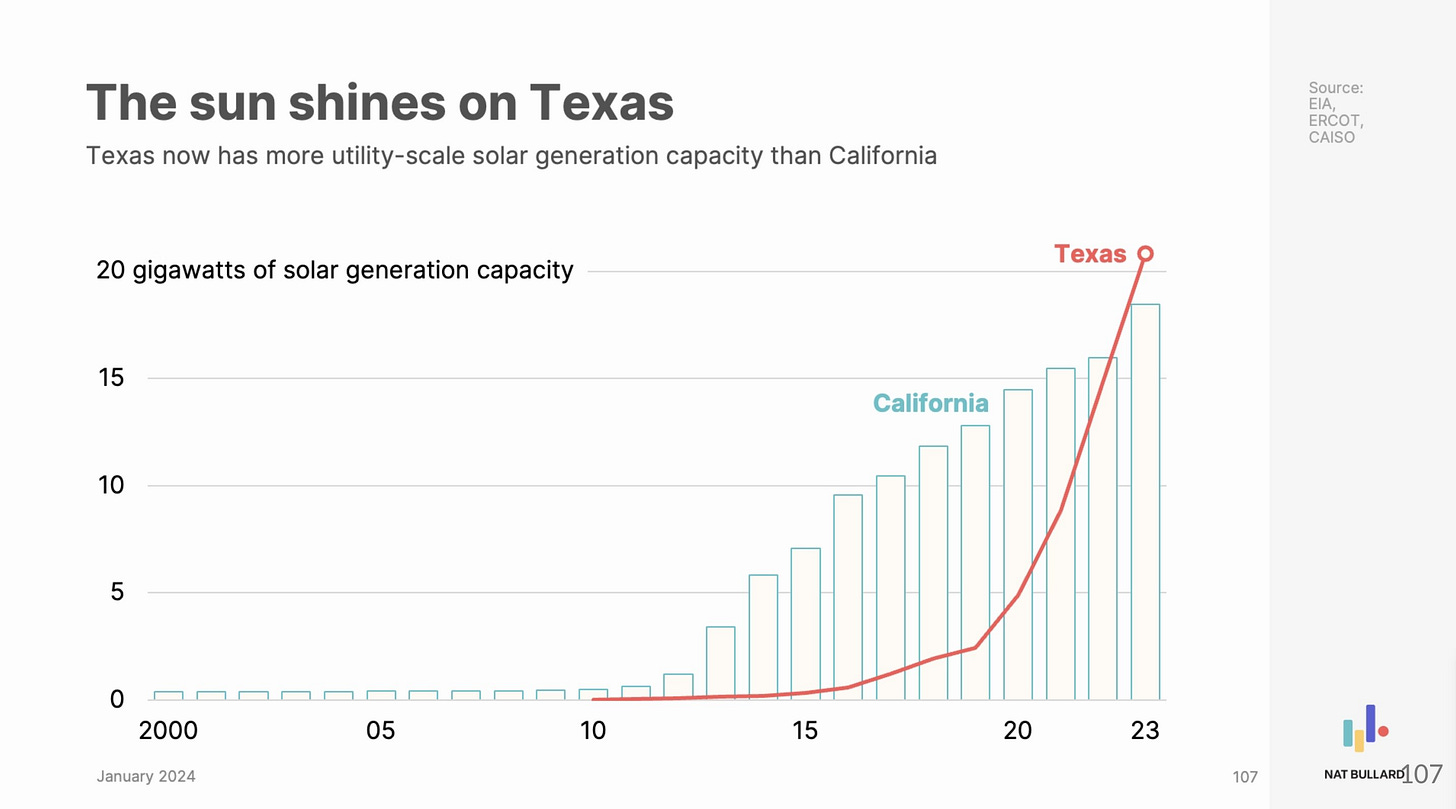

Instead, even the most housing-favorable blue state politicians push aggressive inclusionary zoning mandates and favor subsidized housing over market-rate construction, even though newcomers invariably live in market-rate housing. And it’s the disparity is not just about housing—despite red states’ disdain for ESG and climate change initiatives, they’re still dramatically outbuilding blue states in clean energy infrastructure as their structural bias toward building things trumps ideology.

I would also not be surprised to see more explicitly partisan-aligned real estate developments—and even new towns—emerge in future years. New Founding’s Highland Rim Project aims to build several conservative-aligned towns in Kentucky and Tennessee in the coming years. And while Silicon Valley draws a lot of attention for dreams of new cities, most actual new towns and cities that have emerged in the US in recent decades have been remarkably conservative.

And anyone with a consumer brand—including real estate operators and entrepreneurs—will need to be conscious of their brand’s political coding. Hard times are ahead for companies and brands that get this wrong. The best brands will navigate this with careful messages and symbols, semiotic indicators of alignment without alienation. (We’ll have more to say on this in a letter coming out in few weeks.)

Partisan sorting is not inherently bad; people should be able pick the communities in which they live for whatever reason they choose. But it is problematic if it leads to an ungovernable nation with no consistent culture or identity. And America does have real external threats. From Noah Smith yesterday:

But even if China doesn’t attack Taiwan and World War 3 never begins, the U.S. is in serious long-term peril. The leaders of both China and Russia clearly have imperial aims, seeking to reconstitute some approximation of their countries’ 19th-century empires. Those dreams will outlive Xi and Putin. And both China and Russia recognize that, Trump or no Trump, the United States of America is their biggest rival and the most important long-term threat to their imperial ambitions.

The New Axis will therefore seek to weaken the U.S. any way that it can, in order to reduce the threat. The first step, of course, is to defeat, dominate, or subvert America’s allies — Europe, Japan, Korea, Australia, India, and the UK. But that won’t be enough for the new imperial powers to feel secure. To fully neutralize the long-term threat from America, they will want to impoverish America’s economy, sabotage its infrastructure, and disrupt its internal social and political stability.

Impoverishing America will involve cutting it off from trade or forcing it to trade on unfavorable terms. No matter what Trump might think, the U.S. can never be self-sufficient in all the things it needs — cut off from critical minerals and export markets, America will be a much poorer nation. So China and Russia will try to do that, by controlling global trade routes.

The solution is to build. To cut red tape, remove burdensome regulations, and embrace abundance—of goods, of energy, and of housing.

Republicans should ensure that their ideology doesn’t get in the way of a good thing. And Democrats should back up strong words with actions. If Democratic politicians really believe that red states are passing draconian laws and infringing on the human rights of their residents, the least they could do is tell their NIMBYs to shut up and tolerate some taller buildings for the sake of humankind.

—Brad Hargreaves

Insightful. Thanks Brad