The YIMBY Army Marches

Developers faced with difficult entitlements are increasingly turning to a new ally: housing advocates

It’s a story every real estate developer knows well.

The community meeting starts at 6pm. After a few housekeeping items, the architect shuffles to the podium and begins presenting. Two-hundred thirty two units, a hundred sixty parking spaces, breaking up the massing, set back, twenty percent affordable…

Jeers follow. One by one, local residents share their concerns. Several believe it’s too tall. Others agree it’s too tall, but also believe it’s too wide. More are concerned about overcapacity at the local school, which recent hit its lowest enrollment since opening in 1973 and had to lay off three specialty teachers due to a lack of students. Another commenter is concerned the project does not end capitalism.

Every attendee is opposed.

The local council member, whose vote is required for the project to move forward, sits anxiously in the front row. She knows there’s a housing crisis—rents in her district have increased by 30% over the past four years, and rental vacancy is under 5%—but given the community’s concerns, she’ll need to scale down the project, add parking, and increase the affordability requirement. The developer protests that the project no longer pencils, but the politics are what they are.

The political winds, however, may finally be shifting. Small groups of advocates are changing the temperature of these local conversations by advocating for housing rather than against it. From its origins in San Francisco a decade ago, the Yes In My Backyard movement is now making its presence felt in community meetings across the country, counterbalancing local NIMBY narratives.

Much has been written about YIMBY, including here in Thesis Driven. We’re not going to cover the basics today. Rather, this letter will tackle more practical questions facing developers across the country: can these groups be harnessed to get my project approved, and how are the politics of housing changing?

An Atlanta Story

Mike Greene had a problem.

His firm’s project, Amsterdam Walk in Atlanta, was facing stiffer-than-expected opposition. With a proposed 1,100 units of housing across a twelve-acre site, the project aimed to add apartments to one of Atlanta’s traditionally single-family neighborhoods.

“We knew it would be a tough re-zoning,” said Greene, SVP Development at Portman Holdings. Traditionally, Atlanta had developed density along a tight north-south axis approximately following I-85. “Go much east or west of that and you quickly get to single-family homes, and the city has historically avoided rezoning single family lots. It’s been an unspoken, sacrosanct thing.”

Despite being only half a mile from the high-rises of midtown Atlanta, Greene’s site was on the east side of Piedmont Park, putting it in on the fringes of an affluent, single-family neighborhood. “At one point a fellow developer sent me the website of a local YIMBY organization,” said Greene. “I glanced at it and put it aside, as I was focused on building support among local stakeholders.” And he initially found success, getting local civic associations on board with the project. But local opponents had other plans.

“We picked up a group of NIMBYs that weren’t part of the civic associations, and they used Facebook, Nextdoor, and Change.org to create a whole lot of noise,” explained Greene. “While there were only about 50 die-hard opponents, they used technology to make themselves look tremendously larger than they actually were.”

When Green initially responded by hosting more public meetings, the plan backfired. “Opponents would show up and collect names of other concerned people attending for information. They were able to amplify their message in a way that was garnering attention of councilpeople.”

“I didn’t think that would be the case,” said Greene. “Maybe I was a bit naive.”

Under pressure, Amsterdam Walk’s support among elected officials came into question. “Councilpeople asked, ‘don’t you have any supporters?’ People from the civic associations would show up at public meetings to show support, and they’d get shouted down. And I don’t mean in a snarky way, I mean shouted down. And there’s only so much even civil leaders are willing to be abused for a project”

At an impasse, Greene reached out to the YIMBY group he had heard about the year prior. Familiar with the project, local advocates sprung into action. “The YIMBYs, the affordable housing advocates—their voices were incredibly important,” noted Greene. “They sent emails and letters. Some of them talked to councilpeople they knew. There was stuff in the news about them. It was particularly helpful when the advocates had a genuine connection with the councilpeople and could say ‘I know you’re catching flak, but this neighborhood has very little space that can be converted to housing without replacing single-family homes.’”

In April, the Atlanta City Council approved Amsterdam Walk by a vote of 8-6 over objections from the local councilperson.

“To the extent that groups like YIMBY can persuade their local membership to make even a small public display, that goes a really long way in a place like Atlanta,” said Greene. “A focused group has a rally to support higher density housing. If you get the right press coverage there, it makes a lot of NIMBYs in a neighborhood look pretty foolish.”

From San Francisco to the World

While there’s no formal hierarchy of YIMBY organizations, San Francisco-based YIMBY Action is the closest there is to a national pro-housing organizing coalition. (Abundant Housing Atlanta, the local branch of YIMBY Action, helped push for the approval of Amsterdam Walk.)

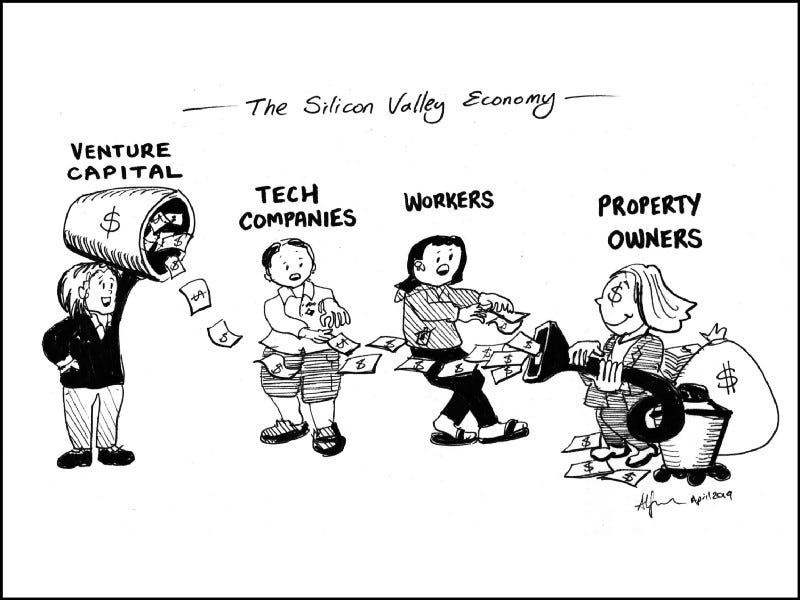

Much like the YIMBY movement itself, YIMBY Action’s origin story begins in San Francisco when high school math teacher Sonja Trauss founded the Bay Area Renters’ Federation, or BARF, in 2014. The Post-GFC, pre-pandemic San Francisco Bay Area faced a housing crisis unlike anywhere else in the states, and Bay Area activists were early to realize that restrictive zoning played a big role in perpetuating the problem. Seminal articles like Kim-Mai Cutler’s 2014 piece How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained) fueled growing normie interest in zoning as a driver of high housing costs.

In the coming years, the loose group of Bay Area housing activists would coalesce into YIMBY Action as a formal pro-housing political force. “We needed a brand my mother would be comfortable with,” explained Laura Foote, Executive Director of YIMBY Action.

“In housing, there hadn’t been that political force that clapped when politicians did the right thing and booed when they did the wrong thing,” explained Foote. “We needed to build that visible constituency.” In practice, this meant a combination of behind-the-scenes work with local elected officials and public advocacy for individual projects, showing up in force at the kind of local community meetings that threatened to derail Amsterdam Yards.

While YIMBY Action initially tackled Bay Area issues—helping elect pro-housing state Senator Scott Weiner and push forward housing projects throughout the region—they quickly evolved into an umbrella organization of sorts for similarly-minded advocates in other cities. “None of this works without local activists excited to run this down the field,” said Foote. So YIMBY Action began providing training and support for local housing advocates, connecting them with local peers and providing the tooling needed to get things rolling organizationally.

Today, YIMBY action has 72 chapters across 28 states and claims to have helped 62,000 units of housing get approved.

As Greene discovered, there isn’t really a formal process for developers to engage housing advocates. “Our chapters make their presence felt, showing up and supporting housing,” said Foote. “Some number of projects come in that way. Some developers read about it in the press and will come back around when they have a housing project. But it’s mostly word-of-mouth.”

As an advocate, Foote would like to see developers get “less timid” pushing projects and advocating for housing on its own merits. “A lot of developers want to tell us about their community benefits package, as if I have any interest in that,” said Foote. “That’s the bribe they’re giving, the spoon of sugar to make the medicine go down. I’m here for the medicine—how many units are we getting?”

“The most common pitfall developers fall into is that they try to speak to their opposition more than they speak to their supporters. If you look at the polling, housing is far more popular than an average Thursday evening planning commission meeting would make you think. But [developers] try to address the concerns of assumed opponents rather than get supporters engaged.”

On the topic of going on offense, Foote’s latest initiative is YIMBY Action’s most ambitious yet: suing California municipalities that violate state housing law. And she’d like to see developers themselves get more aggressive about pursuing all legal options to secure entitlements—options that developers are often hesitant to pursue for fear of upsetting local officials.

“A lot of people did a lot of work to pass these housing laws,” said Foote. “You can get conned into thinking it’s up for debate, but it’s the law.”

On Politics

It is increasingly clear that the politics of housing are changing. Individual projects aside, states red and blue—from Montana to California to Texas to Colorado—are passing legislation to make it easier to build housing. At a national level, leaders of both major parties agree we need more housing supply, although their preferred solutions differ.

It is unfortunate that momentum for reform is coming at a time when the macro environment for building housing is fairly unappealing. Rates appear to be stuck at an elevated level while tariffs and deportations threaten to increase the cost of materials and labor, respectively.

“Policy matters but macroeconomics matter more,” said Greene. “Policy aside, if you can’t make a deal pencil out as an attractive investment to investors—who have an option to invest in anything anywhere in the world—you just have nice words and pretty pictures. I feel like that gets lost a lot.”

So while the current reforms will surely benefit housing production, they would’ve done a lot more good during the decade of generationally-low interest rates from 2012 to 2022. Alas.

The financial feasibility of housing development is often an area where advocates and developers don’t exactly see eye-to-eye. For instance, New York’s local pro-housing organization—Open New York—has come out in favor of aggressive rent control and refuses donations from people affiliated with the real estate industry. (NB: Open New York is not affiliated with YIMBY Action).

As the YIMBY movement grows, maintaining discipline among a loosely affiliated set of independent organizations is a growing challenge. “My unofficial title is cat herder,” said Foote. “Staying single-issue is our single most powerful tool in our toolbox. If you have mission creep, you make your tent smaller. We’re single-issue focused on housing production.” On the matter of rent control, Foote usually avoids engaging. “For us, it’s about whether you can draw a direct line to housing production. If you can show a rent control policy harms housing production, we’ll get involved (against it). But that’s a pretty small number.”

In a sense, the alliance between housing advocates and developers is largely one of convenience. YIMBYs need developers because developers build housing. Developers need YIMBYs because they provide a countervailing voice in local meetings. But to the extent developers hold their projects long-term, they become landlords whose interests are largely counter to increasing housing supply. See the current situation in Austin, where a liberalized zoning code enabled the construction of so much housing that rents dropped by more than 20%.

But real estate developers do not have anything resembling class solidarity, and any individual developer would be happy to add to the housing supply as long as their project still pencils. And as far as YIMBYs are concerned, that’s what matters.

As for getting housing approved, advocates are making an undeniable difference today. “The NIMBYs aren’t as effective as they think they are,” said Greene. “When this was all over, they didn’t call council members and figure out how to keep engaged. They just went back to their keyboards and started complaining about something else.”

—Brad Hargreaves

Love the YIMBY movement. Common sense housing density support is good for cities. 🏙️