Why Your Favorite Real Estate Metric Is Bad (and Good)

There's no perfect way to measure real estate returns. Here are the pros and cons of each metric.

We at Thesis Driven write a lot about innovative real estate models and concepts. But each project’s success or failure ultimately comes down to the same handful of real estate metrics: yield-on-cost (levered and unlevered) and IRR.

Each metric we use to measure real estate returns—projected or actual—has its own advantages and flaws. But too often I see even sophisticated sponsors and investors getting too focused on one metric at the expense of others, creating a skewed perception of the opportunity at hand.

Today’s letter will explore the pros and cons of each real estate return metric. We’ll discuss the interplay between different metrics and how combinations of metrics—such as UYOC, IRR, OER, and equity multiple—can complement each other and paint a fuller picture of a deal.

Want to learn more about how the real estate industry works and the basics of real estate finance? Thesis Driven’s next Fundamentals of Commercial Real Estate course is happening in NYC on October 15-16th, 2024 and virtually starting October 28th. Learn more and sign up here.

The course takes a case study-driven approach to real estate development, exploring “a day in the life” of a developer and her team as they redevelop a 200,000 square foot mixed-use project. We’ve now run this course five times and gotten exceptional reviews and an NPS of 80+, so we’re pretty excited about it!

Metric #1: Unlevered Yield on Cost (UYOC)

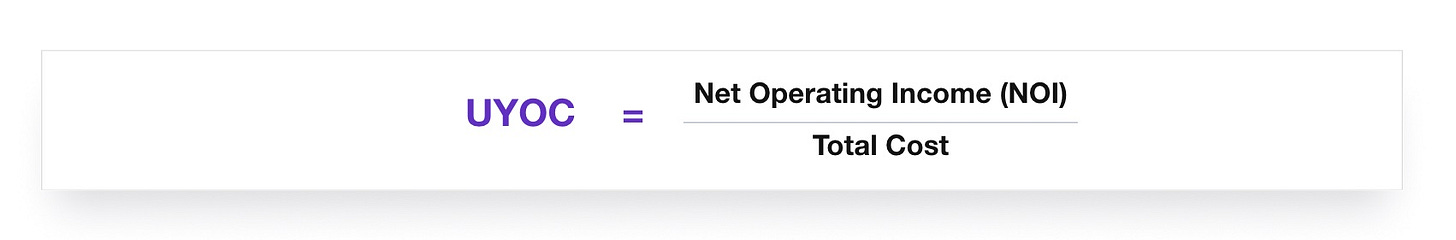

We’ll start with my favorite metric: Unlevered Yield-on-Cost. UYOC is perhaps the simplest metric out there: it’s the Net Operating Income (NOI) of a property divided by the total cost incurred to generate that NOI. For a stabilized, cash-flowing property, “total cost” is simply the purchase price. For a development project, total cost includes the land cost plus any hard and soft costs incurred to develop the asset.

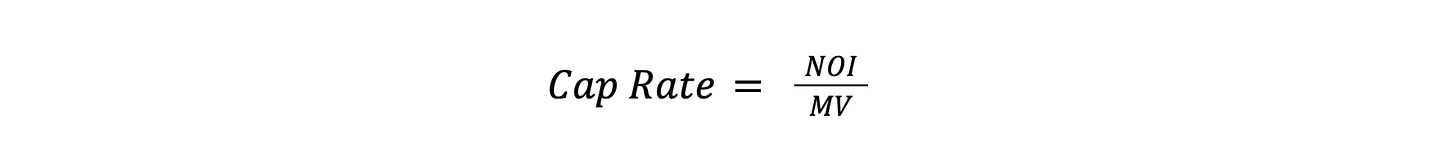

UYOC often gets confused with a similar metric, cap rate. It’s an understandable confusion, as the cap rate equation is quite similar:

“MV” here is the market value of the property. While the cap rate and UYOC equations look similar, “cost” and “market value” are fundamentally different things: cost is what the developer put in to create the cash flow whereas '“market value” is what the cash flow is worth.

In the words of ReSeed’s Moses Kagan, “cap rate is what you buy, yield on cost is what you create.” Ideally, a newly-developed property’s market value is higher than the total cost that went into developing it, meaning that—from the developer’s perspective—the property’s cap rate (upon sale) should be lower than its unlevered yield-on-cost.

You often hear related terms thrown around like “cash on cash yield,” which some real estate investors substitute for UYOC. It’s not a particularly accurate substitution, however, as NOI is not cash flow.

Why it’s useful