Capitalizing Emerging Real Estate with Cloudland

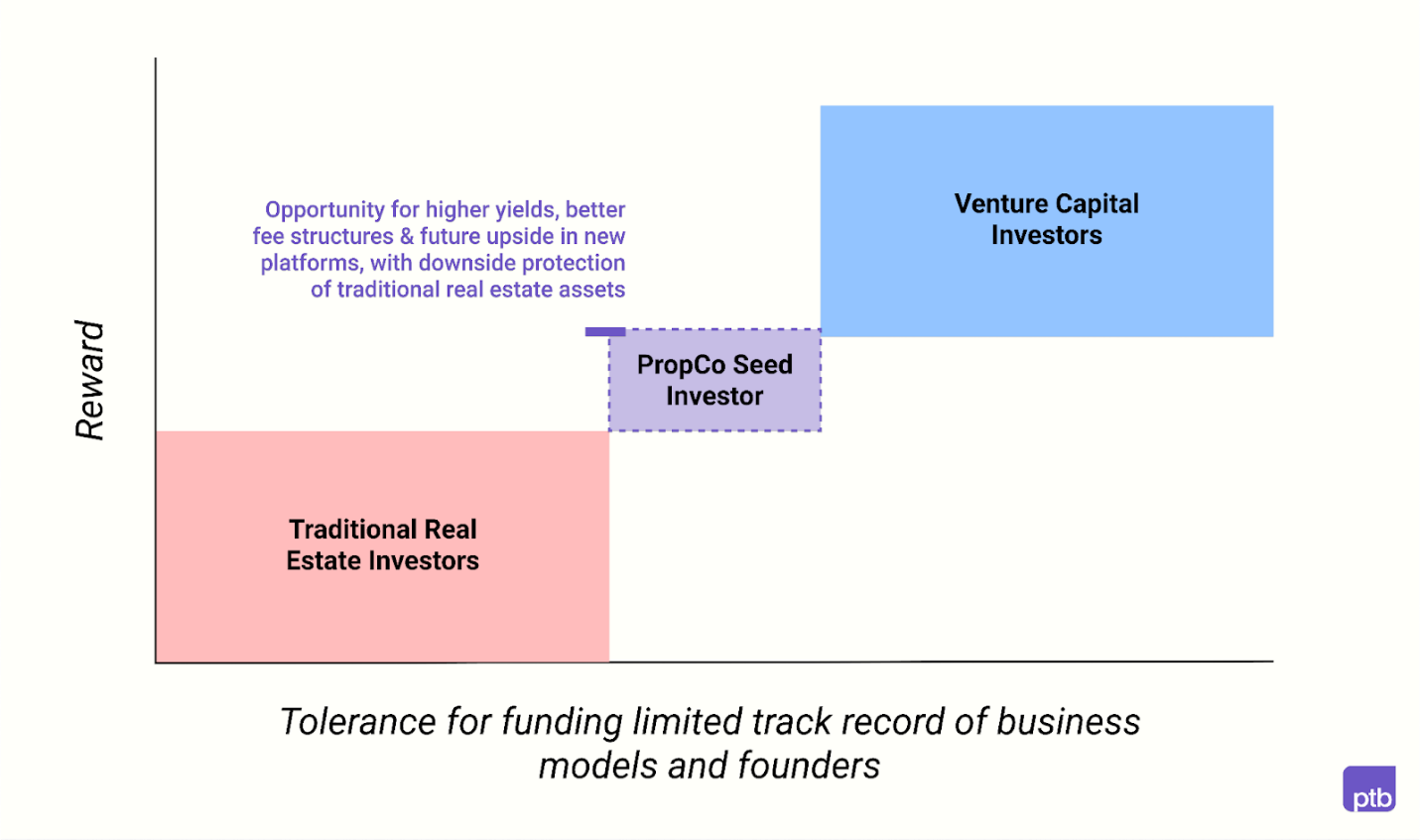

PropCo seed investors are the newest category of real estate capital focused on backing early stage, niche real estate operators

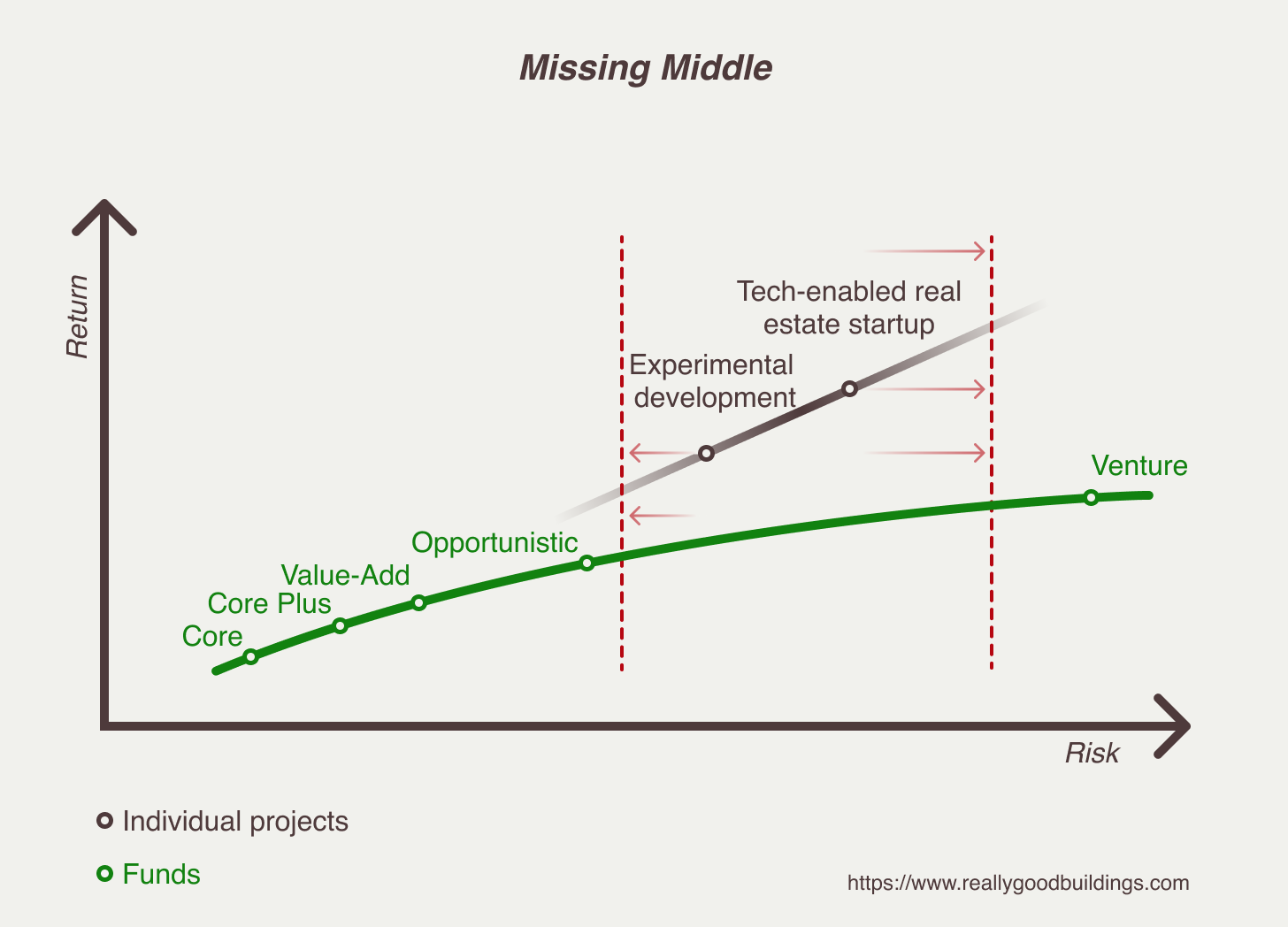

Raising capital for novel, early-stage real estate concepts is not easy. Too small and risky for traditional real estate investors but too slow and uninteresting for venture, financing for emerging real estate operators is a known gap in the market.

But “PropCo seed” concepts aiming to fill that gap are gaining steam, with growing investor interest in backing niche, operationally intensive real estate categories that can generate impressive yields. Among those investors is Jonathan Reindollar of Cloudland, and he’s on a mission to upend real estate private equity by providing a new kind of capital for innovative real estate companies.

Reindollar—along with his partners Matthew Karle and James Gleason—is part of a new generation of platform investors, capital providers who sit between venture capital and traditional real estate equity. They’re willing to go earlier when partnering with emerging operators than most real estate investors but evaluate deals from a real estate perspective, prioritizing strong fundamentals over OpCo upside.

Today’s letter takes a deep dive into the emerging world of platform investors with a focus on Cloudland’s journey. Specifically, we’ll tackle:

Risk / reward imbalances in real estate private equity today;

PropCo “seed” investment models;

Cloudland’s story and approach;

A look to the future and the importance of real estate operators.

A Risk-Return Balancing Act

The past decade has revealed fundamental risk-return imbalances in today’s real estate market.

Here at Thesis Driven we’ve written extensively about the problems faced by innovative real estate operators which fall in an awkward risk-reward gap between traditional opportunistic real estate capital and venture.

But traditional real estate private equity faces its own distinct risk-return mismatches. “Fundamentally, investors have to peel back the layers and ask whether they’re getting a return commensurate with the risk they’re taking,” said Reindollar. “And it struck me that many of the investments that real estate private equity were making were quite poor on a risk-adjusted basis.”

Reindollar is no stranger to the real estate PE business. He has spent over a decade in traditional real estate private equity including five years at Highgate investing in the hospitality sector. But Reindollar had concerns about the growing volume of capital moving into the real estate sector in comparison to the number of viable opportunities.

“Over the past 10 years, $1.3 trillion has flowed into real estate PE. That’s resulted in spreads coming down, driving poor risk-adjusted fundamental valuations and leading to negative leverage and other challenges. There’s just too much capital chasing too few institutional-quality deals.”

That might sound contradictory coming from someone who just raised a real estate fund. But the “institutional-quality” modifier is key—while assets that are large and comprehensible to an institutional investor are getting bid up, opportunities can be found in smaller deals off the beaten path, thematically speaking. This mirrors the broader rise of real estate niches as more esoteric asset categories—think things like industrial outdoor storage, marinas, and RV parks—draw attention from yield-hungry investors souring on the traditional food groups like vanilla value-add multifamily.

Reindollar has an interesting framework for rationalizing the risk-reward tradeoff for Propco Seed Investors. “I think there is the fair perspective that investing with emerging managers and nascent operating companies includes a high-degree of risk. However, if you can acquire quality real estate at below market valuations because you are not competing with the larger institutions, and you can mitigate emerging manager and nascent operating company risk through Cloudland’s institutional lens and experience, then what you have invested in are strong real estate assets or portfolios with above market cash flow profiles. That feels like asymmetric risk.”

“What is riskier, traditional real estate private equity purchasing industrial in 2022/2023 at 4.5%-5.0% cap rates with negative leverage, aggressive rent assumptions, and an underwritten exit in 4 years, or our employee housing investment in the Mountain West which, before closing, we pre-wired a NNN lease to a credit tenant at an initial mid 9’s unlevered yield-on-cost? The difference is there is a large amount of time and energy that go into our smaller deals, and that’s where Cloudland and our operating companies step in.”

Of course, these emerging categories don’t always fit neatly into traditional real estate investing frameworks. In many cases, the checks are small and the businesses are operationally intensive. While a number of new investment models have emerged in recent years to tackle these opportunities, they’re broadly bucketed as PropCo seed investors.

The PropCo Seed Landscape

While there’s no formal definition of a “PropCo seed investor,” we generally use it to refer to real estate investors that put programmatic real estate capital behind new operators with innovative ideas. In many (but not all) cases, these investors also put some capital into the OpCo to get it off the ground. In general, PropCo seed investors are real estate investors first and foremost, and they view any OpCo equity as gravy on top of good real estate deals.

From a risk / reward standpoint, PropCo seed investors generally fall somewhere between VCs and opportunistic real estate investors. As mentioned earlier, this has historically been a gap in the capital markets. Entrepreneurs with novel real estate concepts are generally taking on more risk than (say) those building another 5-over-1 multifamily asset but far less risk than a new software platform, for instance. Yet there have been few investors willing to address this gap; VCs generally look for 10x returns—almost impossible in real estate on 5-7 year time horizons—while real estate investors look for proven concepts.

PropCo seed models generally fall into a few broad categories, often structured as joint ventures or incubations; for instance, Iconiq Capital’s efforts getting Sentral+ off the ground by purchasing the OpCo’s initial assets. But joint ventures can also present challenges. Mynd’s $5 billion partnership with Invesco never really got off the ground after the latter’s focus shifted as interest rates rose. While institutional JVs can offer scale, they’re also subject to all the politics and strategic fluctuations that can come with large organizations—and it doesn’t solve the problem that institutions still need to deploy big checks, putting many niche opportunities off-limits.

Cloudland’s Approach

It would be reasonable to assume that investing in early-stage, niche real estate would require a venture-style, upside-driven approach.

But Jonathan Reindollar and Cloudland are on the other end of the investment spectrum. “Unlevered yield-on-cost is our gold standard,” said Reindollar. “We approach real estate investing from a Ben Graham fundamental analysis perspective. Where in today’s real estate landscape can you acquire assets at attractive valuations with a margin of safety? I don’t believe it's in middle-market real estate private equity.”

Instead, they’ve found yield by focusing on emerging and small-format aggregation opportunities in operationally-intensive sectors. Thus far, they’ve partnered with—and helped build—operating companies to aggregate portfolios in employee housing, strip center retail, industrial outdoor storage, and vacation rentals. To give one example, Cloudland created Blue Hour Housing, a real estate operating company which sources, develops, and manages employee housing properties throughout the US.

Blue Hour’s acquisition strategy is predicated on partnering with employers (hotels, ski resorts, hospitals, mining companies, country clubs, etc.), often signing long-term master leases to house their partners’ employees at converted properties. Blue Hour has developed four properties in Vermont and Colorado through partnerships with Vail Resorts (Vermont), Killington Resort (Vermont), and Climax Molybdenum Mine (Colorado) to date, in addition to aggregating single-family and multi-family homes in Connecticut through a partnership with a national employer.

While Cloudland is willing to back real estate operators (very) early in their journeys, Reindollar is quick to differentiate Cloudland from a venture firm. “We’re the antithesis of venture capital, which likely should not have invested in most operating “PropTech” businesses in the first place. We don’t underwrite OpCo performance in a base case,” he explained. “We’re exclusively focused on driving RE returns.” In fact, Reindollar’s initial investment plan didn’t have any capital going into operating companies, although he eventually settled on a 5% allocation to cover OpCo expenses while the other 95% is invested in real estate itself.

“In addition to long-term upside, the operating company is a means to source and execute real estate returns, but it should not typically expect venture-level exits,” Reindollar continued. “Real estate operating companies can still be great businesses, but we certainly don’t think the cash flow profile of most real estate operating companies warrants venture capital.”

(And most venture investors now agree, with brick-and-mortar models consistently scoring near the bottom of our investor interest polls. But that has left a gap in the market that firms like Cloudland are now filling.)

But since the survivability of the operating company is critical to the real estate returns, Cloudland also evaluates the management company’s unit economics. “If every management contract costs more to service than the operating company is receiving in fees, they won’t be around long enough to sustain this flywheel,” notes Reindollar. In other words, Cloudland is evaluating both sides of the coin: can the real estate generate a return that justifies the risk while throwing off sufficient fees to keep the operating company in business?

While Reindollar has strong opinions on evaluating real estate investments, Cloudland is quite flexible in how they work with real estate operators. “In some cases, we just provide capital and get out of the way. In other cases we’ll build an operating company ourselves.” But providing back-office support—things like bookkeeping, HR, and underwriting—is a part of Cloudland’s value-add.

Otherwise, Cloudland’s relationship with real estate operators looks quite conventional. “We own 90% of the real estate and control major real estate decisions,” said Reindollar. “The operator controls the OpCo, and we earn an ownership share in the operating company as we deploy real estate capital.” In addition to their ownership stake, Cloudland receives exclusivity on funding the OpCo’s real estate—exclusivity that burns off if Cloudland passes on too many deals.

“In general, we soft circle $10-15 million in real estate equity capital for each opportunity,” says Reindollar. Cloudland’s initial fund was $45 million, although they scaled up with co-investors—often their own LPs—as needed in individual deals.

Notably, Cloudland anticipates a long hold period. The firm’s first fund has a 12-year life with three one-year extension options. “We fundamentally believe that real estate was meant to be held over a long duration,” said Reindollar. “Great wealth has been created in real estate through the frictionless compounding of interest over time. What’s happening in real estate PE is the opposite, with recurring transactional costs and shortened hold periods, traditional models are relying on uncertain, short-run assumptions.”

Reindollar believes the long hold period will allow him to maximize the upside from his small-scale aggregation strategy. “In strip retail our yield-on-cost is at a 200-300 basis point spread relative to where REITs are trading at for the same asset classes. If you can materialize that cap rate arbitrage through aggregation, that’s where you can really win.” That is, back an operator long enough to aggregate a portfolio that attracts institutional interest. “We want to find asset classes that are scalable and operating companies that have the ability to scale them.”

It’s An Operator’s World

While almost all PropCo seed investors reject the language and framing of venture capital, they nonetheless share some core beliefs with VCs that differentiate them from other real estate investors.

One axiom of traditional real estate investing, for instance, is that the physical real estate asset is the primary driver of value. While a good (or bad) operator can temporarily change an asset’s cash flow, returns and wealth creation are primarily driven by picking the right asset class and the markets while holding assets long-term.

PropCo seed investors, on the other hand, place far more emphasis on the importance of the operator to find and manage those assets.

“If we believe the power is shifting from capital allocators to operators who can turn $1 into $2 and do so consistently and with real pipeline, we need to be spending a lot of time with those operators and rolling up our sleeves ourselves to create that value.”

In other words, it’s not just enough to buy the right real estate and hold it. Investors have to get their hands dirty. They have to get operational.

While traditional real estate investors might scoff at this Marxist nonsense elevating sponsors’ labor over investors’ capital, there are macro reasons to believe the traditional model of real estate investing may be unraveling. The predictable appreciation of real estate without improvement or operational savvy was somewhat of a uniquely 20th century American phenomenon; it depended on the kind of continuous economic and population growth that we are unlikely to see over the next 50 to 100 years. Generating real estate returns in the 21st century, according to this new cohort of investors, will require a more active approach.

Whether Cloudland’s model seems generous or punitive likely depends on the operator’s perspective. At first glance, Cloudland’s offer to operators seems far less appealing than a typical venture seed round: Reindollar is offering far less operating company capital in exchange for a strategic partnership and deal-level exclusivity. But to a real estate industry veteran, Cloudland’s offer is intriguing: enough capital to get off the ground without spending 20 years working your way up the ladder and putting your house up as collateral. And unlike VCs, Reindollar doesn’t expect his operators to 10X their valuations.

Of course, the capital-light model championed by Cloudland means that operating companies are unlikely to build the 20+-person design and engineering teams rolled out under the venture model. “There’s something healthy to being a bit bootstrapped,” said Reindollar. “You’re forced to make more decisive decisions, and that will create better real estate entrepreneurs.”

“If you have the capital and pipeline to invest in the real estate, the fees those assets produce along with creative bootstrapping and Cloudland resources can get you a long way.”

Reindollar’s approach is reflected in how Cloudland vets entrepreneurs. In addition to evaluating the operating company’s real estate thesis and deal pipeline, Reindollar vets real estate entrepreneurs for—among other things—their grit.

“Those departing real estate private equity all know how to build Excel models. But are you willing to scrub a hot tub?”

—Brad Hargreaves