Is Energy and Building Management Tech Poised for a Big M&A Moment?

Analyzing the future of the sector

Joe Aamidor is a product leader who has spent the past 10 years working with vendors on product-led growth strategies and investors who need additional horsepower during commercial due diligence. Shaun Stewart is a product and strategy executive with over 12 years of experience in commercial real estate and PropTech, leading growth and innovation across startups and scaleups.

Over the past two decades, energy and building management technology has emerged as an indispensable tool in commercial building operations. Startups in this market have consistently shown an ability to raise capital and—in many cases— a tangible return-on-investment to commercial buildings based on energy reduction and equipment cost savings. It's now uncommon to find a major owner or operator not using this type of technology across their portfolio. With an addressable market in the tens of billions of dollars, hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested into dozens of startups over the past 15-20 years.

Despite this, actual success—in the form of exits and capital returned—has been lacking. Some of the top companies in the sector raised venture capital more than 10 years ago, so investors, founders, and management teams alike are increasingly impatient and wondering “What’s next?”

Today’s letter will attempt to answer that. We have looked across the sector to project the potential for M&A and other outcomes using a data set composed of two dozen companies that have collectively been deployed in over four billion square feet of commercial building space and raised over $684 million to drive reductions in energy cost, longer equipment life, and more efficient facility operations.

We will:

Introduce four growth- and capital efficiency-based quadrants to help assess individual startup performance and future opportunities.

Highlight dynamics in the vendor landscape that have limited growth and success of many startups.

Discuss specific strategic options for firms, based on their current scale and capital efficiency.

Market Dynamics

Before diving into the M&A landscape, it’s important to understand several key dynamics in the building and energy management tech sector:

From a buyer’s perspective, the market is crowded with vendors that appear largely undifferentiated. While many firms highlight specific technologies or features, buyers report similar ROI and payback periods across the board.

Large portfolio owners often work with multiple vendors across properties—due to decentralized purchasing decisions or changes in ownership—leading to fragmented tech stacks.

High switching costs (e.g., replacing meters, sensors, or BMS connectors) combined with limited perceived differentiation have made buyers reluctant to change vendors. As a result, competitive wins are rare.

This has left many startups “treading water”—generating enough revenue to survive but not enough to scale, invest meaningfully in R&D, or displace incumbents.

These dynamics point toward increased M&A activity over the next 12–18 months. However, while many deals have been explored, few have closed. A core challenge is assessing the relative position of firms in this fragmented landscape. Who should be acquiring? Who should exit? Which companies are best positioned for consolidation by OEMs or private equity?

These are the central questions that will shape the next phase of M&A in the sector.

Startup Capital Efficiency Analysis

Consider two example firms with similar product offerings which started around the same time. One (Firm A)has scaled to 500 million square feet deployed, while the second (Firm B) has struggled to get to 50 million. They’ve raised about the same amount of capital but have had very different outcomes. In fact, the smaller firm may be valued at significantly less than it has raised. These types of scenarios are common across the industry today.

In particular, we believe Firm B’s story is particularly common in the energy and building management software space today. Many industry observers predict more M&A, but would Firm B want to sell today? It isn’t at risk of going out of business in the near term. And it’s unclear there are any viable buyers of Firm B at a price they’d be willing to accept.

So while the market remains fragmented and organic growth is slowing, that does not automatically mean there will be more M&A. Through this analysis, we’ll predict where the energy and building management market is headed, including the potential for consolidation and strategic acquisitions.

Our analysis takes fundraising data and total square feet deployed for two dozen firms in this space, placing each startup on a matrix. These two metrics are readily available (though self-reported). Based on knowledge of the industry—and findings by other researchers, such as Lawrence Berkeley National Lab—the revenue these firms generate per square foot are very comparable, making the analysis directionally accurate.

We then divided each firm’s total capital raised by their total square feet deployed to calculate a capital efficiency metric. Finally, we graphed each firm’s capital efficiency against their total square footage to develop four distinct cohorts, then conducted an analysis of cohort-level dynamics to better understand potential outcomes for firms.

Further available evidence supports this approach. For example, most firms in our “Leaders” quadrant regularly post job openings, show steady headcount growth over time, and engage in regular marketing campaigns and social media activities. By contrast, many firms in our “Emerging” quadrant have no job openings, show flat or declining headcount over time, and have generally low activity on social media. Our data is yet another set of metrics that confirm what many working in the space know: there are a few leaders, and many firms that simply haven’t figured it out yet.

Our analysis does not include names of individual firms, and we plan to add more firms to this analysis in future iterations. For more details on the mechanics of the analysis, see our newsletter post about this analysis.

Summary dynamics

These market dynamics also have a profound impact on the buyers. A typical commercial building facility leader procuring a relevant solution will have a few dozen firms from which to choose—each firm with paying clients and a real product.

Moreover, it is rare to see conquest sales. Since vendors typically have high retention, they can continue operations even if they aren’t growing. Vendors cite similar ROIs, deployment approaches and timelines, and comparable value propositions. These firms have differentiated products (e.g., a proprietary algorithm) but undifferentiated value.

In addition to many firms stagnating, there also has been a pullback in venture funding for proptech and climate tech. We also believe that there may be diminishing returns for many startups to invest in organic growth, given their age and lack of breakout growth so far. Investors are realizing this, too. In direct conversations with some investors, there is skepticism of this market segment based on the lack of breakout winners and the poor performance of many firms. Firm B, discussed above, is not the only one that has not grown into a previous valuation (especially true as multiples have come down in recent years). Many firms are treading water and should actively consider their strategic options.

Detailed cohort analysis

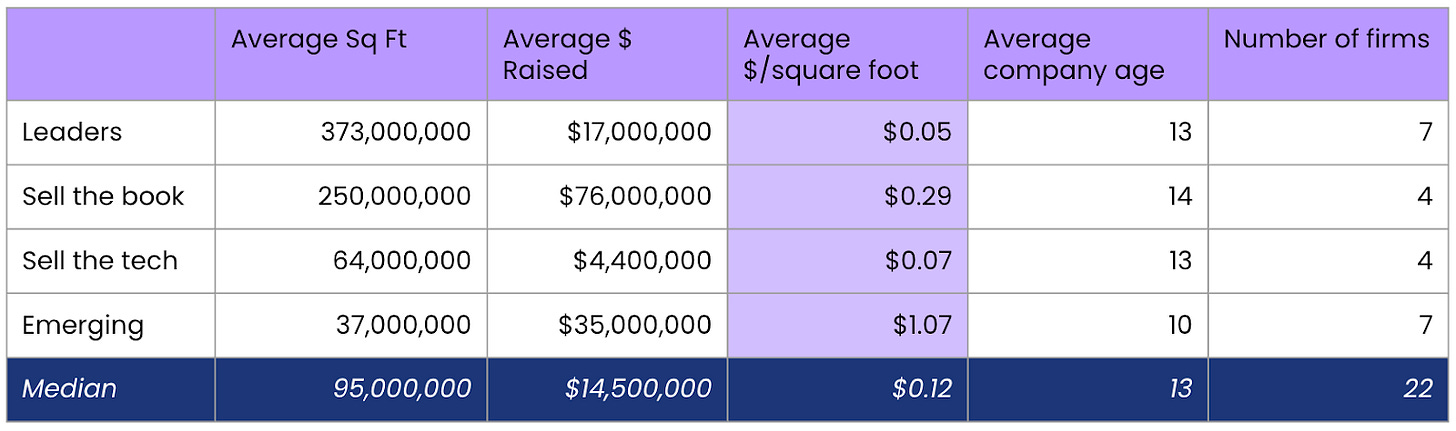

The firms in our analysis can be placed into one of four quadrants that reflect their current success and future prospects.

Leaders are firms with substantial scale and very good capital efficiency. While they may have raised large checks, it has paid off. This group averages 373M square feet and has $0.05/square foot capital efficiency. Based on specific examples in this cohort, one could argue that an ability to incrementally grow over a long period of time (many of these firms were early market entrants) is a better indicator of success than total capital raised. Slow and steady does seem to be winning the race. These firms may be the most suited to acquire smaller peers, but they may also want to stick with the recipe that has worked for the past 13 years: incremental, thoughtful growth that does not require huge sales and marketing expenditures. At the same time, if one of the leaders gets aggressive about inorganic growth - or two leaders merge - this would create a market-making blockbuster that could start closing more conquest sales. The new entity would be very hard to ignore and likely a low-risk innovator that would effectively service clients for years to come. We also think there are other options for these businesses; while they may not seek to sell, they would command higher-than-average valuations.

Sell the Tech are firms that have 20 percent of the scale of the leaders (64M sq ft), but they are nearly as capital efficient ($0.07/sq ft). They have raised much smaller amounts of capital, and have made effective use of those funds. At this point, they may have trouble scaling to the size of the leaders given market saturation, but their offering may be valuable to a larger firm or PE shop that can invest in it and deploy across robust existing sales channels. Early-stage investors that remain bullish on the space should look at this category first.

Sell the Book firms are large (average scale of 250M sq ft), but still have smaller customer bases, on average, than the Leaders. Crucially, they are much less capital efficient ($0.29/sq ft) as they have raised on average $76M. We believe this indicates either a product-market fit issue, or these firms are late to the market (fewer blue ocean sales to close). Moreover, several of these firms have raised large amounts of capital with a plan to invest in sales and marketing - in addition to a product-market fit issue, these firms may have learned belatedly that 9-18 month sales cycles can’t be expedited solely with more sales and marketing resources. Long sales cycles and high switching costs remain fundamental “laws of gravity” in this market.

These firms have difficult decisions. They may have enough scale to indicate some success, but will have trouble raising more money and being a market leader. At the same time, the substantial book of business should be attractive to an acquirer, if a realistic valuation can be accepted. This also means that these firms likely will sell for under their most recent valuation. Tough questions and honest assessments of their future prospects are likely in order for these firms.

Emerging firms tend to be small, about 10 percent the size of the leaders (37M sq ft). They are even less capital efficient than the “Sell the Book” firms ($1.07/sq ft). While these firms tend to be the youngest, they still have an average age of 10 years and may be hamstrung by an artificially high valuation from a prior fundraise. We are skeptical that these firms can challenge either the leaders or the “Sell the Tech” firms. If they had a better solution than the Leaders, it's likely that we would see more growth by this point.

These firms may be able to position themselves for an acquisition based on strength in an asset class, a difficult to develop feature, or geographical strength. These firms may also be a quality bolt-on for a roll-up, albeit at an unappetizing valuation. Firms in this category tend to have little marketing presence, recent reductions in headcount, and few-to-no job openings.

Strategic Directions

This analysis leads to a number of action items for each key stakeholder group. First, startups should figure out where they fit in this framework and where their direct competitors land. If you are a dominant firm, consider how you should approach the competition. This could include a more aggressive conquest sale strategy, but that also may be a capital inefficient decision based on the functional lock-in effects. And, if your peers are significantly larger than you, what is your realistic plan to catch up to their scale? Does an infusion of capital actually get you there, or just make you even less capital efficient? While a capital infusion could delay the pressure to exit for now, it may actually reduce optionality in the long run, making an exit even less viable.

For firms struggling to catch up to the Leaders, an exit may be the best outcome, even if it’s not at a valuation that investors and management would have hoped for. Moreover, there's a real risk that, as consolidation occurs in the market, some firms will be left out when the music stops. That would create a new competitive landscape in which smaller firms will have even more trouble competing with fewer, larger peers.

Second, despite a gummed-up M&A market, potential acquirers do have some actionable targets. This analysis indicates that some firms, especially those in the Sell the Tech category, could deploy new capital effectively, scale their businesses, and deliver a solid return to their investors. Alternatively, they could be good starting points for a roll-up strategy. Additionally, Leaders may be in position to grow significantly and even drive more market consolidation through inorganic growth given their leadership position.

Third, investors should use this framework when assessing new firms, especially for firms that have already raised more capital than peers and have not been able to deploy it effectively. For investors that have already deployed capital into a startup in this category, consider the liquidity strategy—it is simply not realistic to think that every firm has a good opportunity to out-compete peers or be one of the last survivors. Given an average company age across our cohort of 13 years, most companies are able to continue to operate even if they are not growing.

Finally, buyers and users of these technologies should factor this analysis into their procurement decisions. Some of the less performant startups may be the easier and more flexible to work with, but they may not have longevity in the market or an ability to continue to deliver innovative solutions. Given the lack of vendor churn, buyers can use the findings of this analysis as another metric when procuring solutions, especially if they are risk averse and want to find a vendor with long-term viability. Capital efficiency should be a metric discussed with any prospective vendor.

While this analysis doesn’t suggest that firms are at immediate risk of shutting down, failures have occurred in this market. SciEnergy, which raised $69M and reached a $104M valuation, scaled to 150 million square feet and rebranded as FlywheelBI. However, it now appears defunct—the website remains online but hasn’t been updated in years, and only two employees are listed on LinkedIn, both with outdated profiles.

SciEnergy spent significantly on sales and marketing, and, using our metrics, had a capital efficiency of $0.46 / square foot. This puts them in the “Sell the Book” category, but with worse than average capital efficiency and less scale than peers in this group. They are not a significant outlier from other firms in our analysis cohort.

Serious Energy was another early entrant in energy and building management software during the early 2010s, combining a materials business with a software platform. The company raised $140M in venture capital but ultimately retreated to its core materials business before shutting down. Its software assets were acquired by Trane Technologies in 2013. It's unclear how much of the funding supported the software unit or how much scale it achieved, but the company stands as another cautionary tale for industry innovators.

This research also calls into question the focus on technology and solution differentiation instead of value differentiation. While many startups have developed their own proprietary technology, such as algorithms and data sets, it does not appear that these investments alone deliver standout growth and returns. Moreover, most firms cite energy savings as the key value proposition and have similar ROIs for their technologies. It is clear that a differentiated solution is not nearly as important as an ability to deliver differentiated value. This differentiated value could be based on more energy savings, lower upfront investment, much faster time to value, among others.

We plan to continue refining this analysis alongside industry stakeholders. We'll also examine the role of incumbent solution providers, which operate at much greater scale than startups and continue to invest in technology. Finally, this research raises a broader question: is the SaaS model the right approach for delivering these capabilities in this industry?

—Joe Aamidor and Shaun Stewart

Great piece. But the cited example of SciEnergy/FlywheelBI may require correction, as I believe Steve works for Generate Capital. So, it could have been an acquisition or acquihire, and the platform is now part of GC.