Two years ago we argued that PropTech needs to die. The term, at least, had become overused to the point of uselessness, describing everything from vertical SaaS companies to low-carbon materials to short-term rental operators.

Today we have a new target: the “emerging manager.” Much like ‘proptech,’ the emerging manager has been overused to the point of meaninglessness, encompassing everything from upstart real estate entrepreneurs looking to buy their first asset to teams of grey-haired real estate veterans moving from family office to institutional backing—all depending on who you ask.

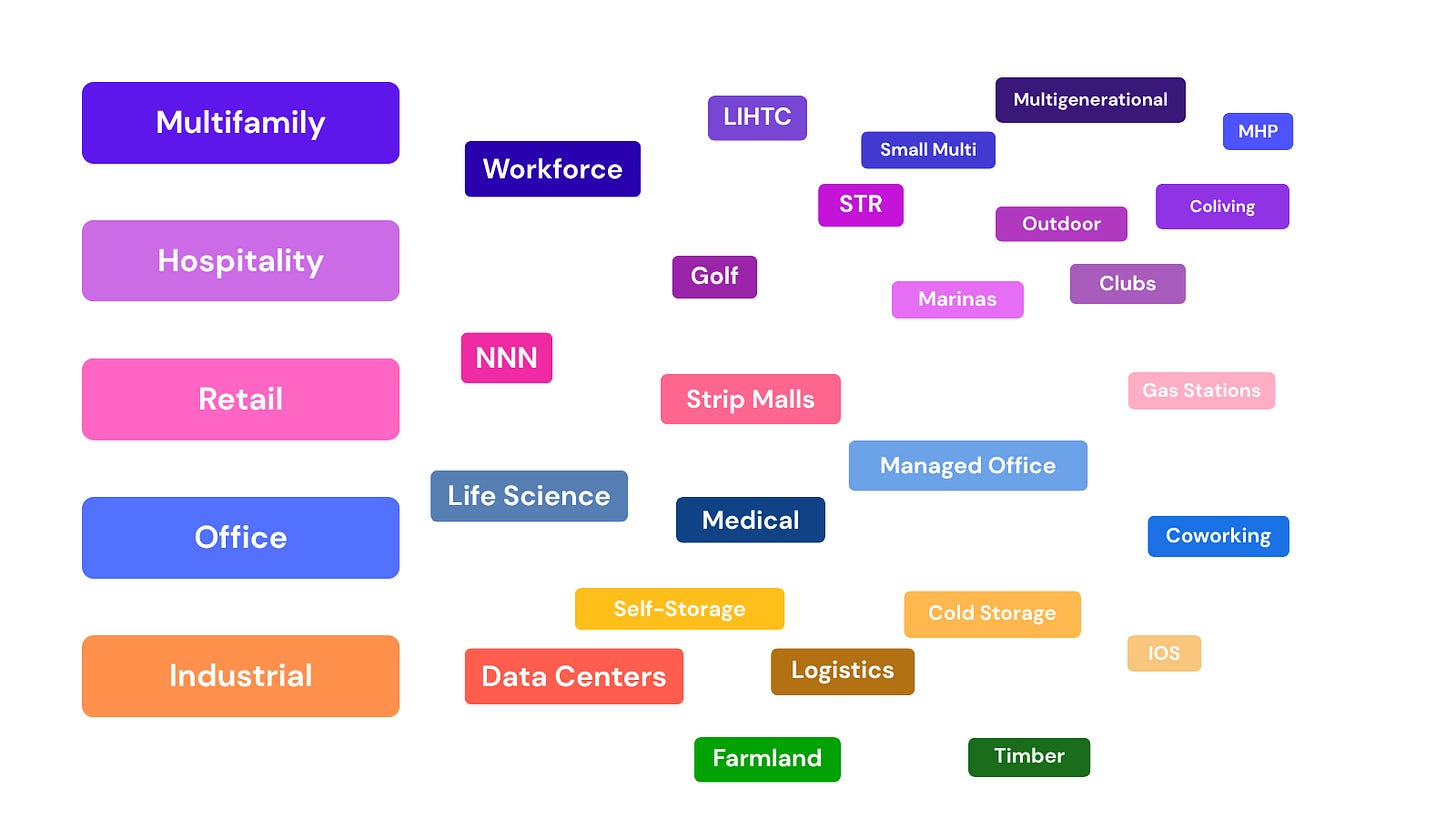

Asset classes suffer from a parallel problem. To some institutional investors, data centers—a $400 billion category—is still niche. A fast-moving real estate PE firm, on the other hand, might consider industrial outdoor storage and RV parks already picked over.

This is a problem for us at Thesis Driven, as much of our writing relies on a shared vernacular about what makes a new category or operator interesting. This is particularly true for our new, investor-only Buy Box letter.

So today we’re going to tackle this head-on, proposing a new taxonomy of real estate operators and asset classes. Specifically, we’ll cover:

The problem with ‘Emerging Manager’;

A proposed taxonomy for real estate operators;

A parallel taxonomy of asset classes;

Thesis Driven’s 4x4 real estate matrix.

We’ll also tease a totally new product we’re working on—one based on this new framework.

An Emerging Problem

The past three years have seen traditional real estate asset classes—vanilla multifamily, office, industrial, and hospitality—lose a bit of their luster. As rates and return expectations rose, the old playbooks and established operators no longer produced the kind of returns sought by investors. Value-add multi, for instance, lost much of its appeal post-2022 as returns weren’t able to keep up with rising rates.

In its place, investors increasingly sought out “emerging” operators as well as less-established real estate asset classes. The riches are in the niches, as they say.

The problem? The same terminology can refer to many different stages and types of real estate operator. Large institutional investors, for instance, occasionally run “emerging manager” programs looking for talent yet-to-be-discovered by institutional capital. As an example, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas—a pension with over $200 billion in AUM—has a large, well-regarded emerging manager program. But they’re looking for operators that have already established themselves in a given sector, with “a preference” to back funds of less than $1 billion.

This isn’t a knock on TRS; it’s great they’re running this program! But its definition of “emerging manager” is relative to its size and risk appetite and will be wildly different from that of, say, an investor like Cloudland, making the concept of an “emerging manager” almost meaningless.

When we at Thesis Driven run our quarterly Pitch Night, we often hear from investors who want to meet “emerging managers” or invest in niche or novel real estate asset classes. For some, that means hearing from established teams of seasoned investors who have each spent the past decade buying and building data centers. Other investors, on the other hand, want to meet the 26-year old generating 14% cash-on-cash yields arbitraging triple-net Buc-ees sale-leasebacks.

There’s no standard vernacular to describe each of these operators and business plans.

It’s a problem, and we’ve decided to fix it.

Real Estate Operators

To replace “emerging manager,” we’re proposing four tiers of real estate operators. These tiers are largely defined by the track record of the operating team—independently as well as together if applicable.

Tier 1: Institutional

The most established tier of real estate operators are institutional-caliber. Typically, this means the principals have taken—and returned—institutional capital (pension and insurance funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, major allocators) during their careers and have often been operating real estate for over a decade.

These operators know the ins and outs of dealing with institutions as well as how to position investments to suit institutional preferences.

Tier 2: Proven

Proven operators have successfully raised, deployed, and likely returned capital at a meaningful scale, but they have yet to raise institutional dollars. Perhaps they’ve been doing deals for 7-15 years, and they’ve built a reputation in an asset class or market. To date they’ve probably raised capital—either deal-by-deal or into a fund—through family offices, syndications, or partnerships with real estate private equity.

When institutions talk about “emerging managers”, they’re usually referring to this tier of operators.

Tier 3: Rising Stars

Rising Stars have successfully raised and deployed capital—probably deal-by-deal—but have yet to establish a track record. When courting new investors they can point to the assets they’ve acquired and their pipeline but cannot yet speak to consistent returns and a history of “round tripping” investor capital.

Despite a lack of lengthy track record, Rising Stars are differentiated from Upstarts (the next category) by having shown they can deploy capital and operate assets. Rising Stars typically are poised for breakout growth once they prove out their initial portfolios, often pioneering new niches and operating models.

Examples: Cardinal Lands, Beach Street

Tier 4: Upstarts

Upstarts are the newest operators. They range from “entrepreneurs with an idea” to operators well on their way to becoming Rising Stars with real pipelines, initial teams, and an asset or two already acquired. They may have a strong thesis, but they have yet to demonstrate that they can repeatably acquire and add value to deals.

Example: Most operators at Thesis Driven’s Pitch Night

Real Estate Asset Classes

As with operators, real estate asset classes range from institutional to nascent, so a common vernacular is needed to describe each asset class as it works its way up the institutional ladder.

Tier A: Institutional

Institutional-tier assets have liquid markets, established cap rates, robust investment sales and capital markets brokerage coverage, and numerous public and private funds / REITs dedicated to the asset class. They’ve demonstrated performance across multiple cycles; investors understand how they perform in good times and bad.

There are relatively few institutional real estate asset classes: vanilla multifamily, office, retail, industrial, and hospitality. That’s it.

Tier B: Established

Established asset classes are on the verge of becoming institutional but typically lack the Tier A’s seasoning across multiple cycles. And while they’ve likely attracted investment sales and capital markets interest from major real estate services firms, they don’t yet have the depth of coverage of the big institutional categories.

Most Established asset classes are attracting some institutional interest but still retain the returns, upside, and excitement necessary to draw larger real estate private equity players as well as family offices.

Single-family rental is probably the best example of a category in the process of jumping from Tier B to A—as evidenced by AFIRE’s latest institutional investor survey.

Examples: SFR/BTR, Data Centers, Life Science, Medical Office, Cold Storage

Tier C: Breakout

Breakout categories are typically off institutional radar—but perhaps not for long. These categories have may have demonstrated operational success and high yields, but a lack of large portfolio trades establishing market cap rates as well as seasoning across multiple cycles have prevented larger investors from entering en masse. It also may not be clear how to deploy significant quantities of capital into these asset classes.

In general, Breakout asset classes are the domain of family offices and adventurous real estate private equity investors.

(For what it’s worth, this category is Thesis Driven’s editorial sweet spot.)

Examples: Outdoor Hospitality, RV Parks, Small Multifamily, Short-term Rentals

Tier D: Formative

Formative asset classes are conceptually interesting—and may have shown promise on individual assets—but are yet to demonstrate repeatable operational success and/or the opportunity for investors to deploy meaningful amounts of capital in the category. Formative categories may not yet even have clear definitions as to what the asset class *is*, with different operators pitching their own visions.

These categories tend to be well off the radar of institutional investors. They’re typically backed by high-net worth individuals and family offices that have taken a liking to the idea.

Examples: Maternity Hotels, Cohousing, Car Condos, Funeral Homes

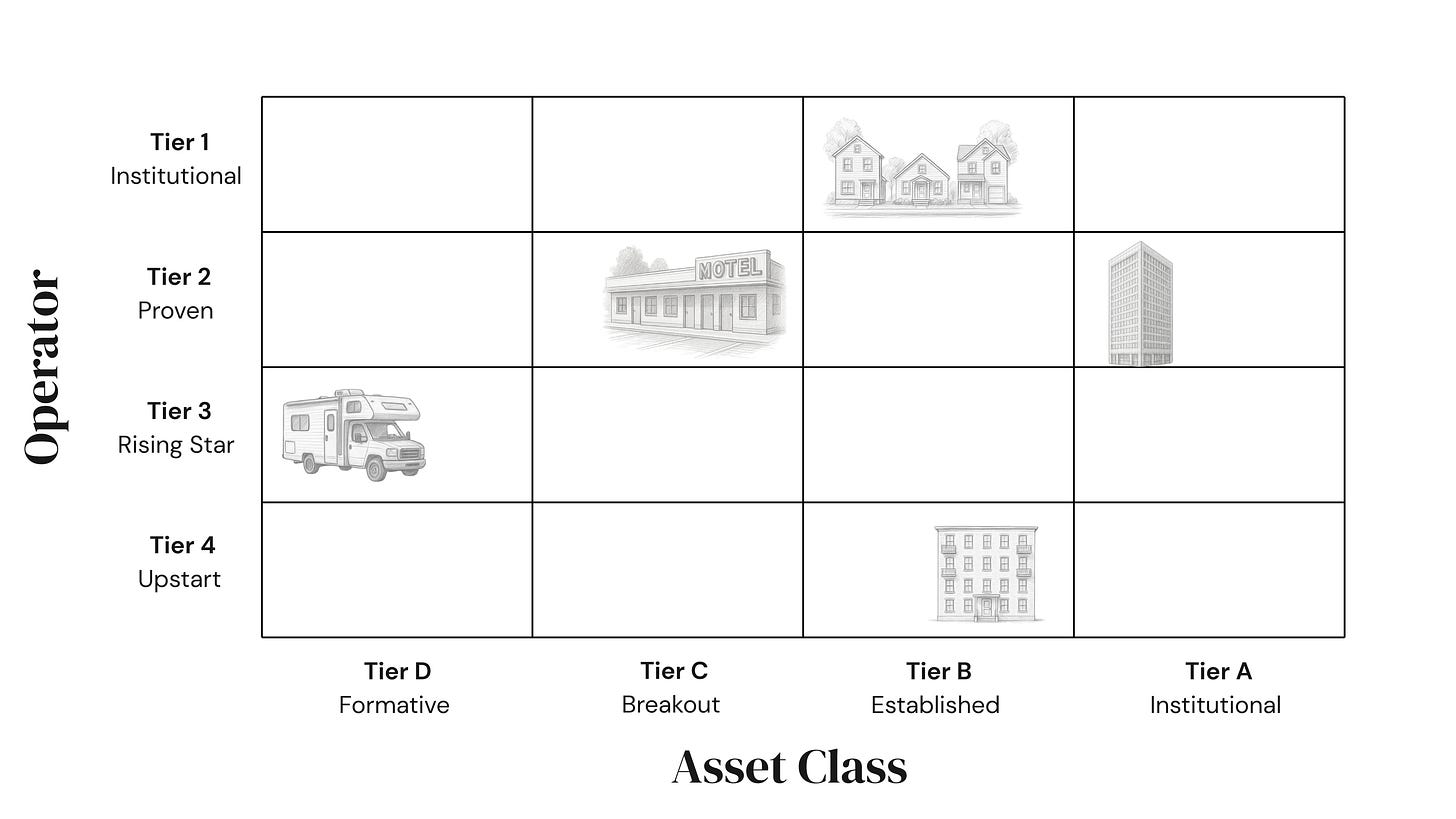

Mix and Match

When used in combination, the tiers form a framework for real estate investors to clearly communicate their “buy box” to the market.

For instance, a pension fund looking for “emerging managers”—defined as operators that don’t already have institutional capital—but are unwilling to leave the beaten path of institutional asset classes are likely interested in category 2A (Proven operators, Institutional asset class) with perhaps secondary interest in 3A (Rising Star operators, Institutional asset class) or 2B (Proven operators, Established asset class).

A family office looking for alpha and yield, on the other hand, is more likely to focus on Breakout or even Formative asset classes—likely categories 2C, 3C, or even 3D.

It’s worth noting that some squares are pretty unlikely—specifically, the upper left of the chart. While newer, less proven operators occasionally tackle Established and Institutional asset classes—think small operators getting into industrial or multifamily—it’s unlikely to see an Institutional operator tackle a Formative asset class. (In doing so, they’d singlehandedly bump the asset class up a letter grade—"if they’re doing it, it must be real!”)

It’s also important to note that these categories aren’t a one-way progression—operators and concepts can move in either direction. Coliving, for instance, had emerged as solidly Tier C until the pandemic hit and kicked it back to Tier D. Office, perhaps, risks the rare demotion from the top tier of institutional asset classes.

The Why

While this is certainly a fun exercise, we’re not just doing it for our own entertainment.

As I said, we’ve now been running Pitch Night for two quarters and have made numerous introductions between real estate sponsors and investors. (We’ve also built a lowkey reputation for investors finding real estate operators through Thesis Driven letters, but that’s neither here nor there.)

Later this summer, we’re going soft launching our newest Thesis Driven product: a database of real estate LPs. Rather than documenting the same institutions or attempting to wrangle the long-tail of retail investors, we’re focusing on the categories of investors most likely to back Tier 2 and 3 operators and asset classes: innovative family offices and real estate private equity funds. We’re also going to pair it with an invitation-only matchmaking service.

Doing this, naturally, requires a shared understanding of who is looking to invest in what—both operator and asset class. And “emerging” only gets you so far in an increasingly complex industry.

If you’d like to be an early user of the LP database, you can sign up here.

—Brad Hargreaves and Paul Stanton

Aha, now I know. I'm an Upstart Breakout Small-Multifamily Emerging Manager! My VC backed HeroHomes.com is a type of "Zillow.com/Realtor.com meets Groupon.com on steroids." To get 200+units institutionally investable multifamily scale, we find, educate, pre-pre-qualify, pre-sell-to, and empower COHORTS of our fellow 18+M military vets with the unknown to us fact that we can use our no-money-down (i.e. 100% LTV) VA Loans to build, rehab, or buy, and become owner-occupying landlords in 2-4 family all residential or mixed-use resi income producing properties for both vet and non-vet renters, such that 50+ vets with 50+ quadplexes gets us to the 200+ units. Thus multifamily economies of scale cost reductions and professional management even in semi-scattered sites infill mode. And the elimination of single-family zoning via "missing middle housing" in California and beyond makes all this very timely. For the developer this eliminates the cost, hassle, and delay of seeking later stage LP investment, and instead moves 10th of that investment to the pre-development (co-GP?) level, but with all the same upside as a full LP investment. Thus with reward far exceeding risk, particularly if the rents are guaranteed by housing-development focused for- or non-profits, government, or foundations who presently are using their too little funds for not enough housing. And a needs no permissions, 100% US Govt, new-wine-in-old-bottles, by precedent up to 48-72% annualized spreads offering, 2-4 units FHA, VA, and USDA loans only pure-play, and thus far superior form of GNMA RMBSs closes the virtuous circle of housing finance. I once got Ray Dalio telling me "We'll take all you can give us" regarding these "HeroMaes," but he's since gone sour on US Govt debt. Better the least ugly bride with a trillion dollar dowry, though, since GSE and Agency MBSs will always be at the core of the core of institutional investing, particularly amongst the conservative life insurance, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds? I welcome talking to potential developers looking to avoid today's version of capitalism, or investors looking to go earlier but for much higher returns. HeroHomes' Mission Statement: "By/for/with locals first to VETrify versus GENTrify the Great American Renewal." Or call it "philanthrocapitalism": "Mother Theresa and Genghis Khan have a business model baby"? reed@herohomes.com 415-342-3634