Assessing Small Multifamily Markets

An operator's analysis of the best places to buy small multifamily buildings

Chris Lehman and Seth Priebatsch are co-founders of Groma, a real estate sponsor and technology company specializing in small multifamily residential properties.

Since the last Thesis Driven letter on the topic, the small multifamily (SMF) asset class has continued to grow and evolve. More institutional capital has entered the market, enabling operators to take advantage of greater economies of scale, and management practices and tech platforms have become more sophisticated.

Despite this progress, SMF’s data and research ecosystem remains underdeveloped. Dedicated research groups like CoStar or ULI produce vast quantities of research and analysis on more traditional asset classes, as do the internal research arms of large real estate investment firms. But because SMF differs in important ways from other asset classes such as traditional (i.e. large) multifamily, many of the outputs of this research will be misleading, or at minimum less relevant, when applied to SMF. Investors’ lack of familiarity with SMF—both at the retail and institutional level—may lead to incorrect assumptions about which markets or individual properties are good candidates for investment.

To address this, we’ve developed a methodology for evaluating geographical markets1 based on their suitability for SMF aggregation2 investment. This letter will:

Provide a refresher on the SMF asset class, revisiting some of the key points from our first letter;

Explain how these dynamics result in SMF aggregation investment having different “ideal market” traits than traditional multifamily investment;

Outline a set of factors that are most relevant to the suitability of a market for SMF aggregation investment, identify metrics to quantify these factors, apply them to major US markets to create metric-specific rankings, and aggregate these metric-specific rankings into an overall weighted market ranking.

In doing so, we hope to provide a resource that brings further clarity to the SMF sector, both by outlining fundamental characteristics of the class and by applying them to the question of how to identify promising markets for investment.

Small Multifamily Refresher

We define SMF as residential properties with 2-20 units.3 There are over two million of these buildings in the US, mostly in dense urban areas. Many of them were built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in response to demand for cheap housing from the millions of immigrants entering the country during this period. Throughout the 20th century, this asset class was held almost exclusively by small, non-institutional owners, many of whom also played an active role in property management. Institutional investors ignored the category, deterred by high operating costs stemming from a lack of centralization and older physical stock.

This changed in the early 2020s. The pandemic caused a sharp, but temporary, drop in demand for urban apartments. This enabled some sponsors to buy into SMF cheaply, experimenting with new management practices and proptech solutions in the anticipation of a market rebound. In many ways, this mirrored the institutionalization of single-family rental (SFR) in the early 2010s in the wake of the global financial crisis/subprime mortgage collapse, but with the added advantage that SMF aggregators were able to adopt many practices originally developed by SFR aggregators. Both SMF and SFR involve many small, physically separated properties that require physical standardization, software integration, and routing/triage algorithms to reduce operational costs while boosting demand.

As operators honed these practices and demonstrated the ability to generate competitive returns, institutional capital flowed into both asset classes. After 15+ years of investment, the SFR space has been bid up sufficiently to have lost the competitive advantage it once had, whereas SMF is much newer and undercapitalized, with <$10B of institutional investment to date versus hundreds of billions in the SFR space.

SMF Market Evaluation

Deploying this incoming capital effectively requires an understanding of the unique factors that make a given market suitable or unsuitable for a SMF aggregation strategy. Many (but not all) of the Sunbelt markets that have consistently topped institutional rankings for the past decade actually fare quite poorly in this regard. While their job growth and overall residential demand growth remain strong, other factors reduce their competitiveness for the SMF strategy.

Small Multifamily Stock

The most important factor for evaluating a market’s suitability for SMF investment is the quantity and concentration of small multifamily properties.

The rationale for the importance of total unit count of SMF properties is straightforward: investing in this class requires economies of scale to succeed, so there has to be a large overall quantity of it available. This favors large metro areas generally and especially markets like Boston or San Francisco that have embraced rules limiting larger residential developments.

Concentration of SMF properties as a percentage of overall stock is important independently from overall scale, as it increases the salience of the asset class from the perspective of brokers and maintenance professionals. The higher the percentage of a market’s residential stock in SMF, the more likely the market will have brokers who prioritize the class as a source of dealflow—both for property sales and rental leasing—and are knowledgeable about its unique characteristics.

Similarly, maintenance techs who frequently service these properties will generally be more familiar with their idiosyncrasies and operational challenges. SMF concentration disfavors large, sprawly markets like Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix and favors smaller, often-overlooked ones like Buffalo or Providence.

Renting Discount

In most metro areas, renting one’s home is cheaper than buying, but the degree to which this is the case varies significantly between metros. In some metros, e.g. Detroit, renting and buying are almost at parity, whereas in others, e.g. San Francisco, renting is less than half the price of buying. Markets where this renting discount is greater are ranked more highly for any investment in rental properties, including SMF, as the relative unaffordability of homeownership makes rental demand less price-sensitive. West coast markets fare well here, while midwestern / Rust Belt markets fare poorly. In the graph below, the renting discount is shown both as a percentage of the buy price and as a raw value.

Fiscal Risk

States and cities vary widely in terms of their fiscal policy. Some tax and spend heavily, others limit both, and still others rack up large deficits, opting to push payment onto future generations. There’s also meaningful variation in where tax revenue comes from—some states don’t tax income or capital gains, instead relying on property taxes, sales taxes, or various other revenue sources.

Not all such fiscal variation is equally relevant for comparing markets for real estate investment. Current property tax rates, for instance, are already factored into current net operating income and therefore into valuations, making them less relevant as a comparative factor independent of financial returns. On the other hand, future tax increases or spending cuts are likely to be factored into current valuations weakly, if at all, but would meaningfully lower future property valuations.

Predicting these future tax changes is therefore a useful way to differentiate geographic markets in a way that is not already factored into current valuations. To do so, we look at two core measures of fiscal risk: government debt as a percentage of income and unfunded public pension liability as a percentage of GDP. Higher levels of indebtedness/pension liability increase the likelihood that taxes will increase or spending will be cut in the future, making the states and cities in question riskier for investment.

Many markets that do well on most of our other metrics fare poorly here, helping push Milwaukee, Richmond, and Indianapolis into the top 10 overall while penalizing otherwise strong markets in California, New York, and Illinois.

Population Density

The vast majority of SMF properties lack built-in amenities, meaning that demand for them is driven primarily by neighborhood characteristics. Density is key here, as dense urban areas tend to have the highest concentration of neighborhood attractions within walking distance. New York City is by far the winner here, with four out of its five boroughs having higher density than fifth-place San Francisco.4

Growth Constraints

Many real estate rankings consider growth-friendly policies a plus, as being able to complete a development project with minimal regulatory obstacles is an obvious advantage. But the buy-and-hold element of the SMF rollup strategy means that these properties tend to benefit from constrained supply, which preserves their market position.

We look at two metrics here. The most straightforward is new housing authorized per thousand existing units; this is the clearest, most straightforward measure of supply constraints in a given market. We also consider a broad index of regulatory constraints on land use, including local zoning policies, urban growth boundaries, environmental standards, inclusionary zoning, and other impediments to new development.

Given the flipped valence of growth constraints relative to the standard investment viewpoint, the relative strength of Sunbelt markets (and especially Austin, which famously implemented major zoning deregulation and saw rents decrease 20+%) decreases, while that of markets in the northeast and west coast increases.

Climate Risk

Our climate risk ranking combines data on natural disasters, flooding/rising sea levels, air quality, and extreme heat/humidity. In addition to worsening resident quality of life and thereby decreasing demand, these factors have a major impact on insurance rates, a core driver of operating costs—especially for small buildings that are older construction and don’t have the scale to justify sophisticated mitigation technology.

Unsurprisingly, this is another demerit for much of the southern half of the country due to ongoing warming. Chicago also fares poorly, with both elevated flood risk and low air quality.

Fundamentals

This metric is relevant to both large and small multifamily assets; it incorporates CoStar’s current and future return expectations for multifamily properties5 as well as current metro area job growth. Rust Belt / midwestern markets perform strongly here, with low cost basis, rebounding populations, and numerous exciting opportunities for adaptive reuse.

Institutional Interest

Portfolio exits are a major driver of overall financial performance, meaning that sponsors need to be confident that they will be able to find a large buyer at the end of their hold period. This provides an advantage to larger, better-known markets, as investors may be nervous about the lack of institutional interest in smaller, less established markets.

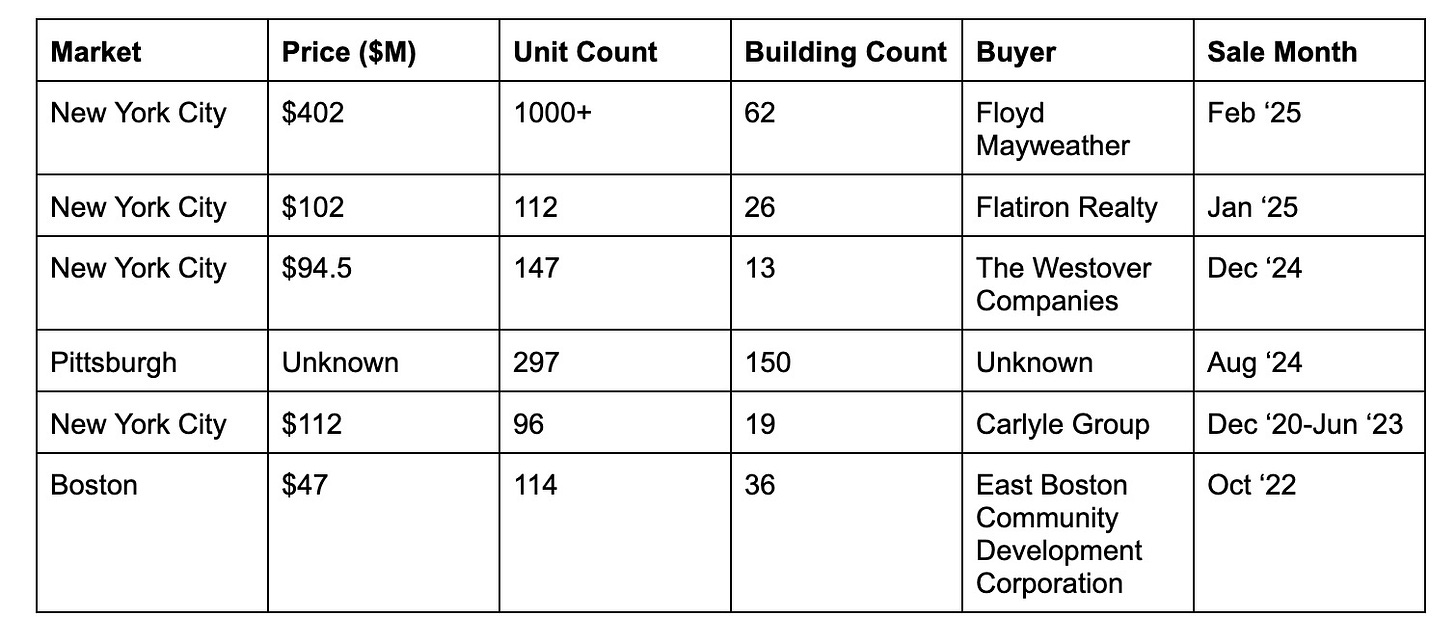

Notable Portfolio Sales

Institutional interest in small multifamily properties is still nascent, but portfolio sales of this asset class to institutional buyers have accelerated over the past few years. Given the importance of the exit transaction to investment performance, these portfolio sales should be seen as a secondary indicator of institutional interest. This is not currently factored into our rankings given that this is a sampling, not a complete listing, of all portfolio sales data for this asset class.

Overall Ranking and Outlook

Small multifamily, unlike traditional multifamily and single-family portfolios, tends to have sales processes tied to life events, personal decisions, and nominal price targets. Over the last few years of relatively high interest rates, institutional sales have slowed to a crawl, as many owners prefer—and are able—to hold assets until conditions improve. More bluntly, traditional multifamily sponsors are often disincentivized from selling unless specific IRR targets are hit, due to aggressive sponsor/promote structures.

These dynamics don’t apply to small multifamily owners. Typically hobby investors, they buy and hold for long periods, often achieving solid—though not institutional-grade—returns. They sell when they’re ready, often realizing what feels like a life-changing gain. This behavior has supported steady sales even during higher-rate periods, creating a compelling seller pool for a new wave of institutional buyers.

Additionally, existing and threatened tariffs continue to affect construction input costs, further limiting new supply in high-demand areas and strengthening the market position of existing assets. Small multifamily, a relatively untapped segment, may soon have its moment.

As mentioned earlier, the lack of quality reporting on small multifamily has been a barrier to large-scale institutional interest. We developed this report to offer an initial framework for analyzing this asset class using traditional research methods, but with metrics distinct from traditional multifamily and single family rental. Our goal in providing this is to enable both institutional and retail investors to invest in this class more confidently. We also expect that facilitating this investment, by providing more reliable exits for missing middle housing developers, will encourage more construction of this undersupplied asset class.

—Seth Priebatsch and Chris Lehman

By default, “markets” are defined based on US Office of Management and Budget metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), using the name of the largest city within a given area as its signifier (e.g. the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington MSA is referred to as “Dallas”). In some cases, smaller areas are broken out, as with the five boroughs of New York City or the Oakland metropolitan division.

Here, “small multifamily aggregation” refers specifically to the approach of buying and operating existing small multifamily properties. This is in contrast with the approach of building new small multifamily properties, which would require a different set of metrics, especially regarding regulatory barriers to new development.

For data availability reasons, the Small Multifamily Stock metric uses properties with 2-19 units given US Census Bureau categories. We expect little difference in rankings from this discrepancy relative to the 2-20-unit definition used elsewhere.

To avoid biasing towards the New York City boroughs, this metric uses population density for the primary city proper rather than the overall metro area for other markets.

Because CoStar’s returns data apply to multifamily properties broadly, rather than just small multifamily, they play a modest role in our overall ranking. Rigorous return projections for small multifamily, were they to exist, would be weighted much more heavily.